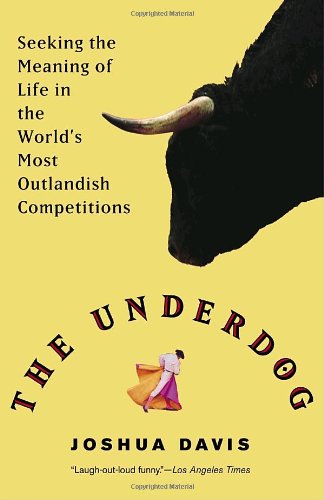

Articoli correlati a The Underdog: Seeking the Meaning of Life in the World's...

Joshua Davis dreams like most guys. He wants a fun career, exciting adventures, a happy wife who’s proud of him, and really big muscles that strangers can’t help but admire. Too bad he’s a 129-pound data entry clerk whose wife, Tara, has only three simple requests for their life together: direct sunlight, a dining room, and a bathtub.

Since none of these exist in their 250-square-foot San Francisco apartment, Josh sets off on a quest to become the provider his wife wants him to be. The problem is that he does it in a way that most people in their right minds would never consider: he enters the most grueling and unusal contests in the world.

In The Underdog, what begins as a means to get Tara her bathtub evolves into a charming story of courage, adventure, and just a little bit of insanity. On the heels of a fourth-place finish (out of four contestants) in the lightweight division of the U.S. National Armwrestling Championships, Josh gets a spot on Team USA and travels to Poland to face “The Russian Ripper” in the World Championships–and Tara finds herself wishing her husband would go back to data entry. Unfortunately for her, he’s just getting started.

Over the next two years, Josh ventures to Spain to try his hand at bullfighting, sumo-wrestles 500-pound men, perfects his backward running in India and at the Golden Shrimp “retrorunning” race in Italy, and bonds with his family at the Sauna World Championships–because sometimes it takes a blistering 220-degree sauna to bring loved ones together.

By turns hilarious, harrowing, and inspiring, The Underdog documents one man’s ballsy attempt to live the American dream to the extreme.

From the Hardcover edition.

Since none of these exist in their 250-square-foot San Francisco apartment, Josh sets off on a quest to become the provider his wife wants him to be. The problem is that he does it in a way that most people in their right minds would never consider: he enters the most grueling and unusal contests in the world.

In The Underdog, what begins as a means to get Tara her bathtub evolves into a charming story of courage, adventure, and just a little bit of insanity. On the heels of a fourth-place finish (out of four contestants) in the lightweight division of the U.S. National Armwrestling Championships, Josh gets a spot on Team USA and travels to Poland to face “The Russian Ripper” in the World Championships–and Tara finds herself wishing her husband would go back to data entry. Unfortunately for her, he’s just getting started.

Over the next two years, Josh ventures to Spain to try his hand at bullfighting, sumo-wrestles 500-pound men, perfects his backward running in India and at the Golden Shrimp “retrorunning” race in Italy, and bonds with his family at the Sauna World Championships–because sometimes it takes a blistering 220-degree sauna to bring loved ones together.

By turns hilarious, harrowing, and inspiring, The Underdog documents one man’s ballsy attempt to live the American dream to the extreme.

From the Hardcover edition.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

L'autore:

Though young, Joshua Davis has accumulated a lifetime of failures. In grade school, he electrocuted himself while trying to construct a fully operational replica of the USS Kitty Hawk in his bathtub. In high school, he started a rock band and at the first and only performance forgot the lyrics of the band’s one song; the group disbanded. After college, Davis directed a feature-length film about a group of friends living in northern California; the movie was bought by a shady distribution company in Nicaragua. The plan: Recoup the investment by showing the indie film on Panamanian buses, The distributor soon declared bankruptcy, never paid for film, and Davis went to work as a data entry clerk at the phone company.

The Underdog is his first book. In the course of writing it, he snuck into Iraq to cover the war for Wired magazine, for which he is now a contributing editor. He lives in San Francisco with his wife, Tara.

Check out the author's website at www.joshuadavis.net

From the Hardcover edition.

Estratto. © Riproduzione autorizzata. Diritti riservati.:

The Underdog is his first book. In the course of writing it, he snuck into Iraq to cover the war for Wired magazine, for which he is now a contributing editor. He lives in San Francisco with his wife, Tara.

Check out the author's website at www.joshuadavis.net

From the Hardcover edition.

Chapter 1

TEAM USA

Grip up!” the ref shouts at me. I am about to face Rabadanov Rebadan—a.k.a. the Russian Ripper—at the World Armwrestling Federation World Championship in Gdynia, Poland. Rebadan is a dark-eyed, hulking torso with emaciated legs. He is one of Russia’s best lightweight armwrestlers and has a reputation for ferocity. Rumor on the floor of this cavernous, Soviet-style gym has it that the Ripper has broken more arms than any other wrestler, and his coach—a gold-toothed man with a blunt, broken nose—is frantically encouraging more such violence. Rebadan snaps his head to the side. I hear his neck crack despite the roar from the thirteen hundred people in the crowd and the jostling of a half dozen photographers. My plan is working. I can tell Rebadan is worried. Or at least confused.

His eyes crisscross my body, looking for weak points. He frowns. All he sees are weak points. I’ve got bony arms, glasses, and strange, spiky rust-red hair that I point menacingly in his direction. It doesn’t make any sense to him. He’s never heard of me. Nobody has. I’m a five-foot-nine-inch, 129-pound data entry clerk from San Francisco named Joshua Davis.

The Ripper slaps himself across the face, willing himself to focus on me. He’s wondering what he’s missing. He blinks. Most of the faces in the crowd also scrutinize me and seem to be asking the same question: “How the hell did this guy get here?”

Well, I earned it.

Sort of.

To most people, the Mojave Desert looks dry and desolate. For me, it’s full of memories. It reminds me of cigarettes, the piss jar, and hours of wordless mind-melding with a Scottish terrier named Ernest. We’d usually head out of L.A. in the afternoon. It was the late seventies and my mom and her best friend, Carole, acted like they were already famous. They were beautiful, on the cusp of being discovered, and with their billowing scarves and oversized shades, they looked like stars, at least to me.

I was just the kid so I got jammed into the Mercedes’s luggage space with Ernest, unseen to the world. The car was a flashy two-seater convertible—Mom and Carole looked great in it but it didn’t leave me and the dog a lot of room. Ernest coped by sleeping a lot, though periodically he got carsick and vomited on me. I focused on the future. It didn’t smell like dog vomit and Mom’s cigarettes. In the future, Mom was the movie star she wanted to be, Carole found a man who wouldn’t be mean to her, and we drove a much bigger car.

In the present, though, nobody was smiling. A trip to Vegas wasn’t about gambling for us. Grandma and Grandpa lived in a trailer behind the Tropicana Hotel. Carole grew up on the outskirts of town. This was a trip home and it was always tense. Carole didn’t get along with her parents and Grandpa never seemed happy to see us.

Grandma was excited, but she had learned to mute her feelings around her husband. She came from a blue-blooded East Coast family and majored in French at Middlebury College in the thirties. Her attention was focused on Europe until she met Grandpa, a gardener in New York who had big plans. There was a new town in the western desert, he explained, and it was going to be big. He was handsome and self-assured. He wanted to turn the desert green. She had just read Candide and took the closing advice to heart: “Il faut cultiver notre jardin.” She fell in love and they ran off to start a nursery in Vegas just after World War II.

Mom dreamed big, too. It wasn’t hard for her. She was the oldest of six kids and had inherited ambition and good looks. But, despite having married a well-educated woman (or maybe because of that), Grandpa refused to send Mom to college. He encouraged his first son instead and Mom was forced to find another outlet for her ambition.

She started with the local Miss Helldorado beauty contest and won it when she was seventeen. She went on to win Miss Nevada the next year, and got sent to Miami for the 1962 Miss USA contest. It was her big break. She was getting out of Vegas. She was going to be a star. She was nineteen years old.

After two days in Miami, the judges selected fifteen semifinalists, and Mom was one of them. Stardom was within reach. Backstage, the fifteen lined up to have their hair done for the final round. The hairdresser assigned to my mom thought it would be a good idea to do a poofy, flipped-up modern look. Mom had misgivings, but she was young and the hairdresser was a professional. She decided to trust his judgment.

When she walked onstage, she exuded confidence, but her hair sent a different message. It said, “I’m an alien space being.” The sheer size of it made her face look small and oppressed, as if she were simply the host for the creature living on top of her head. There was such an aesthetic separation between her and her hair that it was still easy to appreciate her beauty. The judges smiled at her, but then their eyes darted up above her forehead and doubt crossed their faces.

She didn’t win. She didn’t even get second. She was the fourth runner-up, and for her it was worse to have had a taste of glory, to have been that close. Of the five finalists, she was the first called to center stage. She was asked to stand on the bottom step while the other three runners-up were announced and led to the higher steps. And finally, Miss USA was crowned right in front of her eyes.

It was a defeat that stayed with my mom for the rest of her life. She took little satisfaction in the four-foot trophy they gave her. Instead, she developed an almost frantic need to get to some finish line first. She chased it for the next twenty years in New York and Los Angeles but always slinked back home through the Mojave as a runner-up. She was in Vogue, Life, and New Woman, but was never the cover girl. She landed a part in Funny Girl, but they made her wear a hat made out of a bushel of wheat and told her it was a nonspeaking role. It didn’t help that she split up with my dad when I was three. She was always almost happy, almost successful—always the runner-up.

It gnawed at her. So much so that she began prepping me at a very young age to be a champion. She wanted me to do what she couldn’t. She said it was because she was trying to give me the opportunities that she never had, but somehow I always knew that it came down to that moment on the stage in Miami in 1962. The photograph of the contestants hung as a reminder in the darkest part of our hallway. The trophy was kept hidden in storage.

To my mom’s credit, she didn’t specify which field I was going to be a champion in, though she did obsess about my posture and teach me to walk a fashion runway. But she never told me what to be. She just waited for my particular genius to manifest itself.

She waited, waited some more, and then started to get frustrated. By age six, I wasn’t demonstrating any particular genius or even heightened physical skills. I liked hiding. I was particularly good at concealing myself beneath piles of laundry, but, because I was so good at it, she never appreciated that talent.

And so we would roll through the dry late-afternoon smog into the desert to present ourselves in front of Grandpa’s severe, silent gaze. Mom wanted to get there and back as fast as possible, so we pissed in a jar and drove a hundred miles per hour. The Mojave was a blur of tumbleweeds, a mason jar of yellow-orange piss, and cigarette ash.

When Grandpa died in 1992, the Mojave took over his role. It stared at me with unblinking, disappointed, burned-out gray eyes. My mother still believed in me—she had nothing else to pin her hopes on—but hope in the desert is usually called a mirage. The desert had given up on me a long time ago, so I kept my distance from it.

Then, two years ago, I got trapped. I had driven to Telluride, Colorado, from San Francisco to visit a friend and now the friend asked if I could take him to L.A. on my way back. I had been his guest and couldn’t say no. It would have been too difficult to explain why I didn’t want to drive through the Mojave. Plus, I figured that we’d be talking the whole time and I wouldn’t even notice where I was.

I could feel it approaching as we descended through Utah. The air dried out and the desert began to suck all the moisture out of me, as if it wanted to sift me down into a pile of dust to show me what I was really worth. My friend fell asleep. I poked him in the ribs, but he kept sleeping. I was left alone with the desert.

I knew I wasn’t worth much. I had eight hundred dollars in my checking account and the balance kept dropping. I had quit my job as a data entry clerk at the local phone company to try, one last time, to find something I was great at. I decided to try journalism—maybe I could be a Woodward or a Bernstein—but I was only making about two hundred a month writing for a free weekly paper in San Francisco. My first big assignment was to write a review of San Francisco’s best strip clubs.

Tara, my wife, was not pleased and wouldn’t let me go to the clubs during business hours. I viewed the assignment as my big break but was forced to do my reporting first thing in the morning, when no one but the droopy-eyed managers were around. My reporting was limited to comments about the menu: “At BoyToys you can munch vanilla plantain prawns while watching continuous strip shows!” I was far from success. Very far.

Though I had given in to her reporting constraints, Tara was still not happy. We lived in a 250-square-foot apartment that received no direct sunlight. I wrote my articles underneath our dorm-room-style lofted bed. She wanted the American dream—a nice home, a regular income, and a gainfully employed, respectable husband. That wasn’t me, and heading into the Mojave only made that reality starker and more painful.

I pulled off the road and stopped at a diner in Needles, California. I needed some water—everything about me felt dry. As I walked through the doorway, I noticed a flyer advertising “Dennis Quaid and the Sharks.” I stopped to look (Dennis Quaid had a band?) and, underneath, a second flyer announced the upcoming U.S. National Armwrestling Championship in Laughlin, Nevada. The words “Anybody can compete—no entry requirements” jumped out at me.

I could almost hear my grandpa whisper into my ear: “You’ll never amount to much.” In the forties, Grandpa had been in the right place at the right time—Vegas was about to boom and needed a man like him. But he wasn’t a good businessman and rarely got the lucrative accounts. He watched as other gardeners came to town and turned the desert green. He sat on the sidelines and did small jobs. He was there first, had seen the potential, but couldn’t deliver.

Now, in my mind, he was telling me that I couldn’t deliver either. I was desperate, and the Mojave made me vulnerable. Thank goodness I didn’t see a flyer for a bug-eating contest because at that moment I realized that I was going to be an armwrestler. I had a strong premonition that it was my long-awaited, undiscovered talent.

Even if I didn’t win, it would make Tara look at me differently. I could be a macho man—at least for a day. And simply by doing something that I probably shouldn’t, I felt like I was going to make a point to both my mother and my buried grandpa. As long as I was trying, there was still a chance that I could redeem my mom’s loss and silence my grandpa’s doubt.

Tara was incredulous.

“Have you gone completely insane?” she said when I got home and told her my plan. “Do you want a broken arm? What am I going to do with a one-armed husband?”

She’s really beautiful when she’s angry. Her intelligent, dark brown eyes narrow and she stands a little taller with the indignation, pushing her breasts out. I told her she looked good.

“Don’t try to smart-mouth your way out of this,” she warned, using the tone of voice she used on the errant fifteen-year-olds she taught in a local high school. “I’m wise to your tricks.”

It was true. It’s hard to play games with a woman you’ve known since you were sixteen. We met in high school, fell in love in college, and got married a few years after graduation. But she knows me well enough to know that she doesn’t fully understand me and probably never will.

“You need to be looking at the classifieds,” she muttered, losing steam. “Not running off to armwrestle in the desert.”

She knew it was useless. I wasn’t going to change my mind. Her teaching job covered our rent and expenses, so, as much as it annoyed her, we could afford this. I told her that I needed to keep trying to find something I was good at. If I just gave up and took any old job, I’d be as unhappy as I was at the phone company and it would be no fun to be married to me.

“But why armwrestling?” she pleaded, pointing out that I’d never armwrestled in my life.

“Exactly! I could be great and just never knew it,” I said.

“Honey, I’m sorry but it’s just really, really unlikely,” she said, eyeing my bone-thin arms. “You’ll win when hell freezes over.”

Two weeks later, I fueled up the baby-blue Buick LeSabre we had inherited from Tara’s grandma and headed back out into the desert. Tara had to teach, so I was on my own in the 115-degree heat. The dryness didn’t bother me as much this time. I felt more secure now that I had a goal. And without a coating of dog vomit the trip seemed easy.

From the Hardcover edition.

TEAM USA

Grip up!” the ref shouts at me. I am about to face Rabadanov Rebadan—a.k.a. the Russian Ripper—at the World Armwrestling Federation World Championship in Gdynia, Poland. Rebadan is a dark-eyed, hulking torso with emaciated legs. He is one of Russia’s best lightweight armwrestlers and has a reputation for ferocity. Rumor on the floor of this cavernous, Soviet-style gym has it that the Ripper has broken more arms than any other wrestler, and his coach—a gold-toothed man with a blunt, broken nose—is frantically encouraging more such violence. Rebadan snaps his head to the side. I hear his neck crack despite the roar from the thirteen hundred people in the crowd and the jostling of a half dozen photographers. My plan is working. I can tell Rebadan is worried. Or at least confused.

His eyes crisscross my body, looking for weak points. He frowns. All he sees are weak points. I’ve got bony arms, glasses, and strange, spiky rust-red hair that I point menacingly in his direction. It doesn’t make any sense to him. He’s never heard of me. Nobody has. I’m a five-foot-nine-inch, 129-pound data entry clerk from San Francisco named Joshua Davis.

The Ripper slaps himself across the face, willing himself to focus on me. He’s wondering what he’s missing. He blinks. Most of the faces in the crowd also scrutinize me and seem to be asking the same question: “How the hell did this guy get here?”

Well, I earned it.

Sort of.

To most people, the Mojave Desert looks dry and desolate. For me, it’s full of memories. It reminds me of cigarettes, the piss jar, and hours of wordless mind-melding with a Scottish terrier named Ernest. We’d usually head out of L.A. in the afternoon. It was the late seventies and my mom and her best friend, Carole, acted like they were already famous. They were beautiful, on the cusp of being discovered, and with their billowing scarves and oversized shades, they looked like stars, at least to me.

I was just the kid so I got jammed into the Mercedes’s luggage space with Ernest, unseen to the world. The car was a flashy two-seater convertible—Mom and Carole looked great in it but it didn’t leave me and the dog a lot of room. Ernest coped by sleeping a lot, though periodically he got carsick and vomited on me. I focused on the future. It didn’t smell like dog vomit and Mom’s cigarettes. In the future, Mom was the movie star she wanted to be, Carole found a man who wouldn’t be mean to her, and we drove a much bigger car.

In the present, though, nobody was smiling. A trip to Vegas wasn’t about gambling for us. Grandma and Grandpa lived in a trailer behind the Tropicana Hotel. Carole grew up on the outskirts of town. This was a trip home and it was always tense. Carole didn’t get along with her parents and Grandpa never seemed happy to see us.

Grandma was excited, but she had learned to mute her feelings around her husband. She came from a blue-blooded East Coast family and majored in French at Middlebury College in the thirties. Her attention was focused on Europe until she met Grandpa, a gardener in New York who had big plans. There was a new town in the western desert, he explained, and it was going to be big. He was handsome and self-assured. He wanted to turn the desert green. She had just read Candide and took the closing advice to heart: “Il faut cultiver notre jardin.” She fell in love and they ran off to start a nursery in Vegas just after World War II.

Mom dreamed big, too. It wasn’t hard for her. She was the oldest of six kids and had inherited ambition and good looks. But, despite having married a well-educated woman (or maybe because of that), Grandpa refused to send Mom to college. He encouraged his first son instead and Mom was forced to find another outlet for her ambition.

She started with the local Miss Helldorado beauty contest and won it when she was seventeen. She went on to win Miss Nevada the next year, and got sent to Miami for the 1962 Miss USA contest. It was her big break. She was getting out of Vegas. She was going to be a star. She was nineteen years old.

After two days in Miami, the judges selected fifteen semifinalists, and Mom was one of them. Stardom was within reach. Backstage, the fifteen lined up to have their hair done for the final round. The hairdresser assigned to my mom thought it would be a good idea to do a poofy, flipped-up modern look. Mom had misgivings, but she was young and the hairdresser was a professional. She decided to trust his judgment.

When she walked onstage, she exuded confidence, but her hair sent a different message. It said, “I’m an alien space being.” The sheer size of it made her face look small and oppressed, as if she were simply the host for the creature living on top of her head. There was such an aesthetic separation between her and her hair that it was still easy to appreciate her beauty. The judges smiled at her, but then their eyes darted up above her forehead and doubt crossed their faces.

She didn’t win. She didn’t even get second. She was the fourth runner-up, and for her it was worse to have had a taste of glory, to have been that close. Of the five finalists, she was the first called to center stage. She was asked to stand on the bottom step while the other three runners-up were announced and led to the higher steps. And finally, Miss USA was crowned right in front of her eyes.

It was a defeat that stayed with my mom for the rest of her life. She took little satisfaction in the four-foot trophy they gave her. Instead, she developed an almost frantic need to get to some finish line first. She chased it for the next twenty years in New York and Los Angeles but always slinked back home through the Mojave as a runner-up. She was in Vogue, Life, and New Woman, but was never the cover girl. She landed a part in Funny Girl, but they made her wear a hat made out of a bushel of wheat and told her it was a nonspeaking role. It didn’t help that she split up with my dad when I was three. She was always almost happy, almost successful—always the runner-up.

It gnawed at her. So much so that she began prepping me at a very young age to be a champion. She wanted me to do what she couldn’t. She said it was because she was trying to give me the opportunities that she never had, but somehow I always knew that it came down to that moment on the stage in Miami in 1962. The photograph of the contestants hung as a reminder in the darkest part of our hallway. The trophy was kept hidden in storage.

To my mom’s credit, she didn’t specify which field I was going to be a champion in, though she did obsess about my posture and teach me to walk a fashion runway. But she never told me what to be. She just waited for my particular genius to manifest itself.

She waited, waited some more, and then started to get frustrated. By age six, I wasn’t demonstrating any particular genius or even heightened physical skills. I liked hiding. I was particularly good at concealing myself beneath piles of laundry, but, because I was so good at it, she never appreciated that talent.

And so we would roll through the dry late-afternoon smog into the desert to present ourselves in front of Grandpa’s severe, silent gaze. Mom wanted to get there and back as fast as possible, so we pissed in a jar and drove a hundred miles per hour. The Mojave was a blur of tumbleweeds, a mason jar of yellow-orange piss, and cigarette ash.

When Grandpa died in 1992, the Mojave took over his role. It stared at me with unblinking, disappointed, burned-out gray eyes. My mother still believed in me—she had nothing else to pin her hopes on—but hope in the desert is usually called a mirage. The desert had given up on me a long time ago, so I kept my distance from it.

Then, two years ago, I got trapped. I had driven to Telluride, Colorado, from San Francisco to visit a friend and now the friend asked if I could take him to L.A. on my way back. I had been his guest and couldn’t say no. It would have been too difficult to explain why I didn’t want to drive through the Mojave. Plus, I figured that we’d be talking the whole time and I wouldn’t even notice where I was.

I could feel it approaching as we descended through Utah. The air dried out and the desert began to suck all the moisture out of me, as if it wanted to sift me down into a pile of dust to show me what I was really worth. My friend fell asleep. I poked him in the ribs, but he kept sleeping. I was left alone with the desert.

I knew I wasn’t worth much. I had eight hundred dollars in my checking account and the balance kept dropping. I had quit my job as a data entry clerk at the local phone company to try, one last time, to find something I was great at. I decided to try journalism—maybe I could be a Woodward or a Bernstein—but I was only making about two hundred a month writing for a free weekly paper in San Francisco. My first big assignment was to write a review of San Francisco’s best strip clubs.

Tara, my wife, was not pleased and wouldn’t let me go to the clubs during business hours. I viewed the assignment as my big break but was forced to do my reporting first thing in the morning, when no one but the droopy-eyed managers were around. My reporting was limited to comments about the menu: “At BoyToys you can munch vanilla plantain prawns while watching continuous strip shows!” I was far from success. Very far.

Though I had given in to her reporting constraints, Tara was still not happy. We lived in a 250-square-foot apartment that received no direct sunlight. I wrote my articles underneath our dorm-room-style lofted bed. She wanted the American dream—a nice home, a regular income, and a gainfully employed, respectable husband. That wasn’t me, and heading into the Mojave only made that reality starker and more painful.

I pulled off the road and stopped at a diner in Needles, California. I needed some water—everything about me felt dry. As I walked through the doorway, I noticed a flyer advertising “Dennis Quaid and the Sharks.” I stopped to look (Dennis Quaid had a band?) and, underneath, a second flyer announced the upcoming U.S. National Armwrestling Championship in Laughlin, Nevada. The words “Anybody can compete—no entry requirements” jumped out at me.

I could almost hear my grandpa whisper into my ear: “You’ll never amount to much.” In the forties, Grandpa had been in the right place at the right time—Vegas was about to boom and needed a man like him. But he wasn’t a good businessman and rarely got the lucrative accounts. He watched as other gardeners came to town and turned the desert green. He sat on the sidelines and did small jobs. He was there first, had seen the potential, but couldn’t deliver.

Now, in my mind, he was telling me that I couldn’t deliver either. I was desperate, and the Mojave made me vulnerable. Thank goodness I didn’t see a flyer for a bug-eating contest because at that moment I realized that I was going to be an armwrestler. I had a strong premonition that it was my long-awaited, undiscovered talent.

Even if I didn’t win, it would make Tara look at me differently. I could be a macho man—at least for a day. And simply by doing something that I probably shouldn’t, I felt like I was going to make a point to both my mother and my buried grandpa. As long as I was trying, there was still a chance that I could redeem my mom’s loss and silence my grandpa’s doubt.

Tara was incredulous.

“Have you gone completely insane?” she said when I got home and told her my plan. “Do you want a broken arm? What am I going to do with a one-armed husband?”

She’s really beautiful when she’s angry. Her intelligent, dark brown eyes narrow and she stands a little taller with the indignation, pushing her breasts out. I told her she looked good.

“Don’t try to smart-mouth your way out of this,” she warned, using the tone of voice she used on the errant fifteen-year-olds she taught in a local high school. “I’m wise to your tricks.”

It was true. It’s hard to play games with a woman you’ve known since you were sixteen. We met in high school, fell in love in college, and got married a few years after graduation. But she knows me well enough to know that she doesn’t fully understand me and probably never will.

“You need to be looking at the classifieds,” she muttered, losing steam. “Not running off to armwrestle in the desert.”

She knew it was useless. I wasn’t going to change my mind. Her teaching job covered our rent and expenses, so, as much as it annoyed her, we could afford this. I told her that I needed to keep trying to find something I was good at. If I just gave up and took any old job, I’d be as unhappy as I was at the phone company and it would be no fun to be married to me.

“But why armwrestling?” she pleaded, pointing out that I’d never armwrestled in my life.

“Exactly! I could be great and just never knew it,” I said.

“Honey, I’m sorry but it’s just really, really unlikely,” she said, eyeing my bone-thin arms. “You’ll win when hell freezes over.”

Two weeks later, I fueled up the baby-blue Buick LeSabre we had inherited from Tara’s grandma and headed back out into the desert. Tara had to teach, so I was on my own in the 115-degree heat. The dryness didn’t bother me as much this time. I felt more secure now that I had a goal. And without a coating of dog vomit the trip seemed easy.

From the Hardcover edition.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

- EditoreVillard Books

- Data di pubblicazione2006

- ISBN 10 034547659X

- ISBN 13 9780345476593

- RilegaturaCopertina flessibile

- Numero di pagine198

- Valutazione libreria

Compra usato

Condizioni: molto buonoMay have limited writing in cover... Scopri di più su questo articolo

EUR 21,27

Spese di spedizione:

GRATIS

In U.S.A.

I migliori risultati di ricerca su AbeBooks

The Underdog: Seeking the Meaning of Life in the World's Most Outlandish Competitions

Editore:

Villard

(2006)

ISBN 10: 034547659X

ISBN 13: 9780345476593

Antico o usato

Paperback

Quantità: 1

Da:

Valutazione libreria

Descrizione libro Paperback. Condizione: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.25. Codice articolo G034547659XI4N00

Compra usato

EUR 21,27

Convertire valuta