Articoli correlati a Mommy Dressing: A Love Story, After a Fashion

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

In the early twenties, if a thing was big, new and deluxe--theater, ocean liner, Paris hotel--it was bound to be called the Majestic. So it was with the grand New York skyscraper apartment house built to look down on Central Park's western rim. From set-back terraces on the upper floors, nestled between the massive Art Deco twin towers, Majestic dwellers could watch the first American zeppelins floating through New Jersey clouds. This Majestic was where my father would take Jo home to meet his family.

She had no intention of being impressed. Central Park West was not Park Avenue. Nor was it the Champs ElysÚes. She knew a little about addresses now. She'd had her maiden voyage to Europe; that made her a woman of the world. Photographers snapped her in a fur coat at Deauville; in ropes of faux pearls at Longchamps; in snazzy spectator pumps at Biarritz.

Back home, too, she was making her moves. The owner of an excellent dress house had picked her out of her class at Parsons to be trained as a designer. She proved to be a whiz at cutting fabric--a natural, like a rookie hitter who knocks the ball out of the park. For the rest of her own long life, Rose Amado of Pattullo Modes never stopped boasting about Jo, her young protegÚe who turned out to be a genius.

The rewards were quick and rich. A salary boost, that dream ticket to Paris, and, finally, the right to call herself a designer.

In the American fashion business then, Paris was the equivalent of boot camp. It was where you went to learn your craft. Not only at the couture showings, but on the streets, in the shops, in the cafÚs and theaters and nightclubs. Montmartre; the Latin Quarter. You learned never to go out without a scrap of paper to sketch on, never to lose your pencil. Knowing how to have your hand kissed, where to daub the new fragrance Chanel No. 5, was part of your homework. The assignment was to acquire chic, and figure out how to translate it into American--for profit. Your boss was depending on it. So was your future. American fashion didn't exist as yet--except in the ambitious daydreams of fledgling designers like Jo. For now, they were strictly French Impressionists; that is, they did their impressions of French ideas, colors, shapes, textures and flavors. The je ne sais quoi that made rich society women cross the Atlantic to be fitted by Schiaparelli, Poiret and Madame GrÞs.

For those who merely yearned to look the way society beauties looked in their Paris originals, American manufacturers did the best they could. Imitation was the sincerest form of flattery, and Paris didn't seem to mind. American dress labels said PARISIAN MODES; and Frenchmen smiled. The couture houses could ban professional spies, or even arrest a pirate who filched sketches and rolled them up in a hollow walking stick. But how could it hurt France if the Yanks thought French dressing was good for everything, including salad? If, indeed, the very word "French," all by itself, could spice up America's love life? French kisses! French ticklers! Ooh, la la! Small wonder that in England at the same time, FRENCH never appeared on anything respectable. Even fine imported porcelain bore the less titillating--and rather disdainful--stamp: FOREIGN. But even English ladies were trying a daub of that Chanel No. 5, here and there. It did wonders.

By the time Jo sailed home from that first expedition, she knew how to tie a scarf around her neck and fling it so that it transformed everything else she had on. It was a trick she used all her life. Like Isadora Duncan. I never saw another American woman who could do it. Not even Jo's own models. Not even me.

She had picked up some useful French phrases, too. The notion of jolie laide was worth learning. It meant ugliness made beautiful through the magic of charm, talent, fire and chic. It described the unforgettable singer Edith Piaf, who looked like a poster child for a wasting disease. It suited Fanny Brice until she had her nose bobbed. It wouldn't have pleased Barbra Streisand a bit, and now, hardly anyone would put up with it. Even in Paris.

There were other careful jottings in Jo's new Paris address book. Where on the rue du Rivoli to find twelve-button glacÚ kid gloves in seashell pink. A coiffeur who understood her hair. A milliner who didn't have to. Fabric and trimmings suppliers; costume jewelers. A dressmaker who would come to the hotel.

She began to memorize what she needed to know--and also what and whom she had better forget, fast. Plenty of charming Frenchmen would dance the spectator pumps off an American girl who looked "smart," and might be loaded. They might be gigolos. Or fortune hunters. Or just . . . French.

Life in New York, meanwhile, was getting to be almost as much fun as Paris. Thanks to Prohibition, there were swanky speakeasies instead of saloons. Jack & Charlie's '21' Club. Harlem night spots where you could go slumming in your faux pearls. Good-looking college men, fresh out of their raccoon coats, were the new men about town, sporting bootleg hooch in silver hip flasks, dancing all night until the city passed a 2 A.M. curfew. One of the young men was my father, movie-star handsome and a smooth talker. He teased Jo, calling her Josephine (because in the song, it rhymed with "flying machine"). He told off-color stories: What's the difference between a preacher in the pulpit and a lady in the bathtub? Answer: One's soul is full of hope . . . She didn't get it, but everyone else laughed. They said he was a card, that Eddie.

They also said what a swell couple they made. And they both knew it was true. When they hit the dance floor, heads would turn. Which was her idea of heaven. It must mean they were in love. Mustn't it?

Ed Regensburg was no playboy, either. Right after graduating from Cornell, he went to work in the family business he would one day inherit, along with his brothers and male cousins. He told Jo that when his lazy fool of a younger brother wanted to drop out of college, his father had thrashed him, saying he would damn well stay there till he graduated--even if he had a long white beard. (In fact he never did graduate.)

Sam Copeland had to appreciate that sort of discipline. Ed's father Ike, however, might not appreciate Sam. Second- and third-generation German Jews, assimilated and prosperous, were also snobs. They had their family cemetery plots with white marble mausoleums. Their built-in humidors were thermostatically controlled. Even their radios were out of sight, hidden inside custom-built consoles with ivory door handles. On high holy days--and only on high holy days--they attended religious services, in English, at a splendid new Reform synagogue. Reform was practically not even Jewish. Next thing you knew, they'd be intermarrying. Abie's Irish Rose was already a hit on Broadway. And songwriter Irving Berlin would soon elope with a society heiress and write "God Bless America."

But of course it wasn't the German Jews who changed their names. Like WASP society, well-to-do German Jewish families tended to marry their own kind. Morgenthaus and Lehmans, Wertheims and Strauses and Guggenheims. The richest of them committed philanthropy on a grand and showy scale: museums, hospital wings; later, centers for the arts and university libraries. E. Regensburg & Sons, my great-grandfather's cigar business, was hardly a copper-and-tin fortune. But it seemed solid enough in the 1920s. Cigars, my father used to say, sold one-for-one with cigarettes at the turn of the century. By the twenties, a good cigar in the hand was a sign of an affluent man. All portraits of the men in his family showed them holding cigars; the equivalent, in a royal portrait, of the ceremonial sword.

In the movies, the fat banker and the crooked politician always kept a cigar clenched in the teeth, and gnashed it whenever they were abusing their power. The bum picked up the stub when the bad guy dropped it on the sidewalk. Years later, when my father was president of the Cigar Manufacturers Association, he tried to lobby Hollywood to show a handsome leading man smoking a cigar. For a brief time there was Robert Mitchum, until he turned out to be a bad boy himself, and got arrested for smoking marijuana.

In real life, a cigar was what new fathers handed out with the announcement "It's a boy!" Cigars were what you served with brandy to the gentlemen, after the ladies withdrew from the dining room. A lucky gambler gave one to clinch a shady deal. Sigmund Freud said it was, sometimes, only a cigar.

But young men of my father's generation were beginning to kick the old man's habit, and take up cigarettes instead. A faster, lighter smoke suited the nervous...

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

- EditoreAnchor Books

- Data di pubblicazione1998

- ISBN 10 0385490534

- ISBN 13 9780385490535

- RilegaturaCopertina rigida

- Numero di pagine261

- Valutazione libreria

Compra nuovo

Scopri di più su questo articolo

Spese di spedizione:

EUR 3,01

In U.S.A.

I migliori risultati di ricerca su AbeBooks

Mommy Dressing

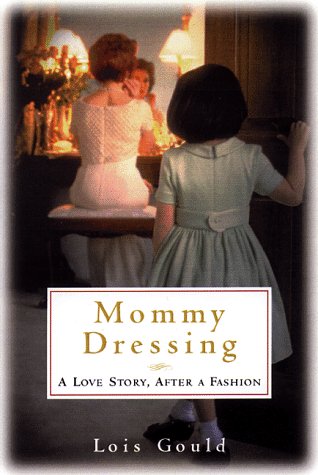

Descrizione libro Hardcover. Condizione: New. Condizione sovraccoperta: New. 1st Edition. Lois Gould's acclaimed bittersweet memoir of her mother, the famous fashion designer Jo Copeland. An intimate inside look at high fashion in the 20th century, an unself-pitying account of a cruel childhood in a rich New York family. Book is Brand New Hardcover 8vo with Brand New DJ. Green cloth spine with gilt lettering; white paper boards. Illustrated with many photos and fashion design sketches. The author's final work prior to her death in 2002. Codice articolo abe-10001

MOMMY DRESSING: A LOVE STORY, AF

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.75. Codice articolo Q-0385490534