Articoli correlati a What Harry Saw

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

1

Here's a fair one: Born blind.

Give that beauty half a moment, see where it takes you. If it isn't near to tears, if you reckon it's just a tragic turn that sometimes happens to somebody else's kid, if you don't damn it as a scabby betrayal of life's promise, then I've grave doubts you deserve the air you're breathing.

Give it another moment. Imagine, if you're able, that you've been struck blind this very instant. Shocking, yeah? You're feeling really sorry for yourself. But you've had your go, haven't you? You are not facing a total blank. You possess images of everyone and everything you ever cared for. You can put together a nice mental video, play it forward or backward just as you please, even freeze-frame the best bits. That should help you keep your grip on the world and where you once stood in it, where you might still stand.

Blind from birth? Could you ever be truly sure you were anywhere real at all? Or would you feel you were wandering in Dreamtime-as the Aboriginals who haven't gone urban still conceive-yet with none of the ancient abo prehension to compass you through it? Not that any of us fully understand this Dreamtime. It's only a word. Some people here like to drop it casually into cocktail chatter, as if that proves they've some spiritual depth within their Prada-sheathed, tennis-toned bodies. Quite a rant I suppose, from a perfect stranger. It's shame, actually. Of the bitterest sort. A long time back in a place I never should have gone I saw a blind baby naked and crawling loose and aimless on the beaten earth floor of a hut. And

I laughed.

I thought of a grub. Couldn't help it. A soft, squirmy grub, that's what the pitiful little creature first brought to mind. I laughed, right in front of the poor kid's mother. I cringe over the reflex still. I expect I'll always regret that cruelty I can never undo or make good.

So I tell myself there are more terrible fates. Born with half a brain, born with heart valves that won't close properly, born with cystic fibrosis or spina bifida, born with that almost inconceivable disease that makes a child look sixty at four and die of old age by nine or ten. Dozens of horrible afflictions.

For kids whose brains and bodies are perfect except for those sightless eyes, I've convinced myself life would be difficult but far from hopeless. It really couldn't be as if you weren't in the world, could it? As you grew, everything would eventually make itself known. You'd feel the ferocious summer sun on your face, the cool relieving winds and fat rain of the westerlies. You'd gradually learn to navigate your immediate geography, and the shapes and textures of objects there, by touch. You'd come to relish flavors: grilled king prawns, maybe, or a perfectly ripe banana, or a nice cold beer. Every day you'd be awash in aromas, from sweet-blooming jacarandas to reeking traffic exhaust, and know the messages they carry. You'd come to recognize tones of affection, or irritation, or joy, or sarcasm, or sincerity, or pity (which you would almost certainly resent) in people's voices. You'd get the news of the day from radio, some ease and enjoyment from Mozart or Górecki, from Midnight Oil or Hunters & Collectors. You'd discover books and the beauty of stories through your fingertips, or the audio versions. No reason you couldn't master any number of trades or professions, up to and including the law or quantum physics, if you were clever enough and inclined that way.

You would never, ever have to dread the coming of night.

And if you struck it really lucky, you might even get to know the lovely intimate smoothness of someone's skin, someone whose body is rich with amazing possibilities, someone whose presence envelopes you with love. Someone with whom you might very well have babies of your own one day.

Someone like Lucy, who gave those gifts to me.

Beyond all that, I've the strongest intimation that not having had a single glimpse of this bloody world would give you the rarest sort of innocence and a wonderful state of grace, for all your life.

Proof? Well, it's pretty bloody funny, isn't it, how many of us with perfect vision would give almost anything never to have seen some of the stuff we've seen. It's hilarious how we go on and on trying any anodyne-from drink and drugs to the Dalai Lama-that might exile certain memories to an area of permanent darkness. If you know anyone at all who wouldn't love to erase a few bits of his life, who doesn't dearly wish certain scenes had never been played, your circle of acquaintances must include a saint.

My personal shortlist for total oblivion? Easy enough. Besides my heartless reaction to one blind infant, there are about three hundred days of my dad's final year of life. Lucy's eyes flashing cold and hard as a diamond for an instant when she told me she was pregnant. A beautiful old violin that never should have been lifted from its case. And a young girl's fall. Falling in a way that never looked like a fall, holding a dancer's line with her body even as a fucking dry-rotted fence slat suddenly snapped under her slight weight high on South Head. Even as she plunged down that sheer cliff, combers hard as the hands of God rising up to crush her.

My name's Harry, by the bye. I'm just on the wrong side of forty now. I've lived in just one place since I was born, which I don't regret though it seems to be a negative distinction in my generation.

Where, exactly? Down under. The Antipodes, the end of the earth-which suits me, because I reckon being so far from anywhere is the chief reason Australia's remained as pleasant and lovely as it has. When we call the place Oz, and we frequently do, it isn't entirely a joke.

My dad lived all his life as well in this same ordinary brick house in a western suburb of central Sydney called Ashfield. His dad had bought the place when he returned from the Great War minus a proper digestive system (thanks to some serious dysentery) and an eye gouged out entire by a Turk grenade fragment.

Dad's own war souvenir was a hole in his left cheek. Nothing really disgusting but still a hole about the size of a bottle cap. You could see a bit of gum and false teeth through it. He was fine eating anything solid, so long as he remembered to take small bites and chew carefully on the right side of his mouth. But liquids were a problem. He had to drink his beer through a straw, which was the worst of it as far as he was concerned.

He acquired that little decoration in a truly pestilential place: the Kokoda Track, New Guinea, 1942. The Japs were battling their way up over the Owen Stanley Range to take Port Moresby. From there it would have been a hop to Queensland, and not a lot to prevent them from raging through Australia like the rabid dogs they'd shown themselves to be in China, Malaya, Hong Kong and everywhere else they'd come calling.

So the Aussie troops were shipped back from the Western Desert to stop the Short Ones on that lone bloody trail over those formidable mountains. What Dad stopped was a pointy little bullet from a Nambu light machine gun that put a cute dimple in his right cheek going in, and made a ragged wreck of the other, coming out sideways with most of his teeth in tow and blowing away so much tissue the field surgeons couldn't close the hole. They just debrided the rough edges 'til they got it fairly smooth, and stretched the skin to make it a bit smaller. Back home, they offered reconstructive grafts to seal up the thing, but Dad said no, he'd enough of army hospitals-a Nambu bullet from the same burst had smashed his hip and kept him in one for a year. And though he would never admit it, to him that hole was what he had instead of a medal. Something to be proud of, something that meant a great deal to all Aussies in those days, though no one cares anymore.

Lucky for him he'd got married before the war, what with that ugly phiz he came home with. No, I'll take that back. I don't think a hole-or a missing arm or leg-would have mattered one bit to that lovely young woman. Even if she'd met him for the first time already mutilated, after his return. For I believe my mother and he were made for each other in every way. Except maybe one, which is why I didn't come wailing into the world until six or seven years after the war ended, their first and last child.

Mum and Dad were a matched pair, as close and understanding a couple as any. That's what everyone said, anyway. Of course I'm likely idealizing a bit. I have no idea how many images of our early days as a family are only received memories. But the abiding feeling I've retained down all these years is a sort of brightly optimistic fifties snapshot: Dad grasping one of my hands, Mum holding the other, me toddling happily along between them, occasionally swung up off my feet, both of them laughing. And both of them smiling down at me, arms around each other's waists, after they'd tucked me in bed nights. The two of them doting on each other, doting on me.

And when I was five or six-old enough so that most recollections of the time can be trusted as my own-they were still that way. First thing Dad would do after returning from work each evening was come up behind my mother, who was always aproned and concentrated on whatever she was fixing for supper, and wrap his arms around her, holding her snug to him until she'd turn to be kissed. That done, he'd pretend he'd just noticed me peering shyly from around the door, stomp over like an ogre, change his grimace to a grin and pick me up, his laughter matching my giggles. Then, while Mum finished the cooking, he'd hold me on his lap and ask about my day. Even when I'd grown a bit too big for that sort of thing, he would always sit me down next to him, offer me one tiny sip of his beer, and listen with genuine interest to what I'd been up to at school or at play.

The only time voices were ever raised in our home was when a few of Dad's mates dropped by. Dad was a pressman at the Herald, a big goer for the trade unions and Labour politics, and so were his friends. Often they'd get excited and very loud about some change t...

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

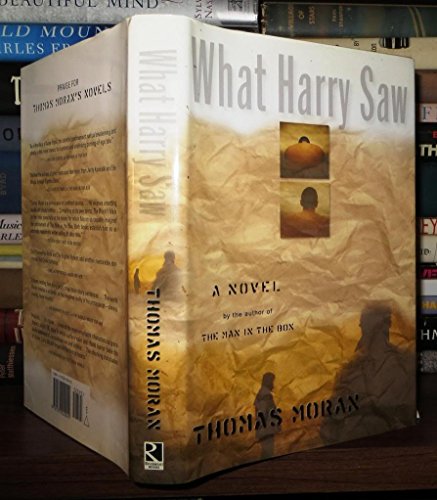

- EditoreRiverhead Books

- Data di pubblicazione2002

- ISBN 10 1573222240

- ISBN 13 9781573222242

- RilegaturaCopertina rigida

- Numero di pagine320

- Valutazione libreria

Compra nuovo

Scopri di pił su questo articolo

Spese di spedizione:

EUR 4,73

In U.S.A.

I migliori risultati di ricerca su AbeBooks

WHAT HARRY SAW

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.3. Codice articolo Q-1573222240