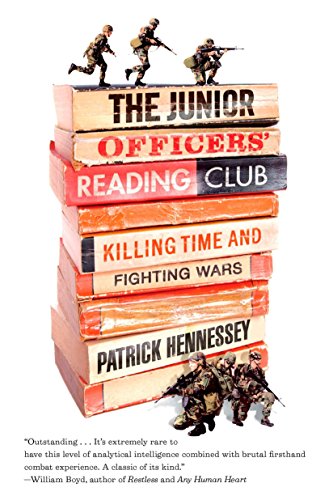

Articoli correlati a The Junior Officers' Reading Club: Killing Time...

Watch a Video

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

The club was a product of a newly busy Army, a post-9/11 Army of graduates and wise-arse Thatcherite kids up to their elbows in the Middle East who would do more and see more in five years than our fathers and uncles had packed into twenty-two on manoeuvres in Germany and rioting in Ulster. ‘Too Cool for School’ was what we’d been called by the smarmy gunner colonel on a course down in Warminster, congratulating through gritted teeth the boys who’d picked up gallantry awards, too old now to win the spurs he never got the chance to while he was getting drunk on the Rhine and flying his desk.

But in a way he was right: what did we know just because we’d had a few scraps in the desert? The bitter, loggy major who sat next to him had probably been to the Gulf back in ’91, when we were still learning to read; probably been patronized himself when he was a crow by returning Falklands vets who in turn had been instructed by grizzly old-timers sporting proud racks of World War Two medals, chests weighed down by Northwest Europe and Northern Desert Stars, which told of something greater than we could comprehend, the stuff of history imagined in black and white when no one was any- one without a Military Cross. Our grandfathers were heroes, whatever that meant, and they had taught the legends who charged up Mount Tumbledown in the Falklands and had returned to teach us.

We who didn’t believe them.

We who had scoffed as we crawled up and down Welsh hills and pretended to scream as we stabbed sandbags on the bayonet assault course. We tried to resurrect the club at the start of our Afghan tour, lounging on canvas chairs on the gravel behind the tin huts of Camp Shorabak. Same sort of base, same sort of desert, just a few thousand miles the other side of Iran. By the end of the first month it was obvious that there would be no club. Each of us, wherever we were and if we could at all, would be reading alone. We went into battle in bandanas and shades with Penguin Clas- sics in our webbing, sketch pads in our daysacks and iPods on the radio, thinking we knew better than what had gone before.

In the end we did and, of course, we didn’t.

________________________________________

Out in Helmand we were going to prove ourselves.

This was our moment, our X Factor—winning, one perfect fucking moment; we finally had a war. From university through a year of training at the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, from Sandhurst to the Balkans, from the Balkans to Iraq, and now from Iraq to Afghanistan, it felt as though our whole military lives had been building up to the challenge that Afghanistan presented.

The only problem was we were bored.

We landed in Kandahar with high hopes. The whole battalion, 600 men, mustard keen to get stuck into the unfamiliar and exciting task of working alongside the Afghan National Army (ANA) for seven months. A task which promised as much action and fulfilment as the last few years had failed to deliver. Of course, there was nothing exciting about arriving in an airfield in the middle of the night, but the taste of Mountain Dew the next morning was the taste of expeditionary warfare.

Yet those first March days of 2007, sitting on the boardwalk, acclimatizing outside the Korean takeaway, watching the many multinational uniforms amble towards the ‘shops’ for souvenir carpets, we had to pinch ourselves to remember this was a war zone. The indeterminate South African accents of the military contractors mixed with the subcontinental singsong of the shit- jobs men jumping in and out of the ancient jingly wagons which rolled haphazardly past millions and millions of dollars’ worth of hardware while the Canadians played hockey on the improvised pitch, and I was bored. As bored as I’d been when I decided to join the Army, as bored as I’d been on public duties, guarding royal palaces while friends were guarding convoys in Iraq, as bored as I’d been once we got to Iraq and found ourselves fighting the Senior Major more than Saddam. Stone-throwing, chain-smoking, soldier-purging bored.

Waiting for the onward staging to Camp Bastion, it was pretty easy to forget that Kandahar was already in the middle of nowhere. A shipping-container city where big swaggering joint headquarters with lots of flags sat side by side with puny National Support Element tents and the luxury of the semipermanent pods of the KBR contractors, who were the real power in places like this. All right, the Taliban weren’t in the wire, but surely Kandahar was at least dangerous enough not to have a bunch of Canadians playing roller-hockey in the middle of its airfield.

Bored of the coffee shop at one end of the complex, we hopped on an ancient creaky bus, drove past the local market, where no doubt the Taliban’s info gathering went on each Saturday as the RAF Regiment juicers bartered for fake DVDs, and hit another café 500 metres down the road. A sign by the bin, overflowing with empty venti coffee cups, announced that here six years ago the Taliban had fought their last stand. A worrying thought occurred: surely we weren’t late again?

From Kandahar we decanted into Hercules transport aircraft for the jerky flight down to Camp Bastion, the tented sprawl in the middle of the ‘Desert of Death’ that was the main British base in Helmand. There we conducted our reception staging and onward integration package under an oppressive and drizzling cloud. The mandatory and in equal measures dull and hilarious set of introduc tory briefs and exercises completed by all British soldiers entering an operational theatre was as vague as ever. All anyone wanted to know was: were we going to be shooting people? and: would we get in trouble if we did? The answers, to everyone’s relief, were ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

________________________________________

After days which seemed like weeks we arrived at Camp Shorabak, the ANA sister camp next door to Bastion. This would be our home base for the next seven months. The photos ‘the Box’—the broad- shouldered commander of the Inkerman Company—had taken on his recce had shown a horizon that symbolized everything Op Herrick (the umbrella name given to ongoing UK operations in Afghanistan) was going to be that previous tours hadn’t been. The view shuffling at night to the loos down in Iraq had been depress ingly eloquent—the burning fires of the Shaibah refinery and silhouetted pipelines told you all you needed to know about that war. The Hindu Kush, on the other hand, was the symbol of the great adventure, the danger and hardship that we hadn’t endured last year. But a bubble of brown and grey cloud blocked out the sky the week we arrived, and we couldn’t bloody see it.

To add insult to injury, it rained. At least in Iraq it had never rained.

The Marines we were taking over from didn’t care. They were going home and had lost too many guys too close to the end of their gritty, six-month winter tour. Patience sapped by working with the Afghans we still hadn’t met, they shamelessly crammed into the gym to work on their going-home bodies, laughing when we asked them questions about what it was like ‘out there’.

We were trying to get to grips with the theory of our task. A normal infantry battalion, the basic building block of any army, works in threes. The basic fighting unit in the British Army is an eight-man ‘section’ (sub-divided into two four-man ‘fire teams’). There are three sections in a platoon—each platoon headed up by

a young whippersnapper lieutenant or second-lieutenant and a wiser, grizzlier platoon sergeant—and three platoons in a company— each company led by a more experienced major and an even wiser and grizzlier company sergeant major. These three ‘rifle compa- nies’ are the basic elements of a battalion, supported by a fourth company of specialized platoons (support company) and a large headquarters company which provides the logistic and planning support in the rear echelons. A tried and tested system forming up a happy family of nearly 700 fighting men, a system which we knew and trusted and which worked.

A system which, for the purposes of our job in Afghanistan, had been thrown out of the window. We were to be an Operational Mentoring and Liaison Team (an OMLT), the set-up of which was simple, but bore no relation to anything we’d ever done before.

Gone was the familiar comfort of the formations and tactics they’d spoon-fed us at Sandhurst. Suddenly we found ourselves in much smaller companies of about thirty, the platoons reduced to mere six-man teams loaded with experience: captains and colour sergeants you would normally expect to find in more senior roles and the junior men all corporals and lance-sergeants who hadn’t been the junior men for a few years. In these teams we were to attach ourselves to an ANA formation and mentor them as we both trained and fought together. Each six-man platoon would be responsible for an ANA company of 100, each company of thirty responsible, therefore, for a whole kandak—an ANA battalion of 600 men—with our own battalion commander no longer commanding his companies but sitting on the shoulder of the Afghan brigadier, advising him on how best to deploy his brigade of thou- sands. We would use our experience and expertise and superior

training and resources to form each Afghan battalion into a cred- ible fighting force. The potential for fun was incredible, the poten- tial for fuck-up immense.

So we should have been glad of the enforced lull at the start, should have been grateful for the time to get our heads around what everyone soon referred to as omelette. But, as weeks passed and the training continued and the cloud stayed down, what we were dreaming of was getting out there and having a fight.

________________________________________

The invite to my going-away party had promised ‘The Great Game, Round III—Beards, Bombs and Burkhas’, but we were getting bollocked for not shaving before early-morning PT, and as for bombs, we fucking wished. It was only a matter of time before the creep ing bullshit would start; before those with nothing better to do would start to patrol the huts, complaining that the mosquito nets weren’t in straight enough lines or that we should be carry- ing our weapons in the showers. The sergeants, infuriatingly tidy and unfailingly up at 0530, would crash around the hut and have us pining for the little eight-man tents we’d resented back in Iraq. Like clockwork they would order ‘lights-out’ at 2200, and the hut would become a profound dull tunnel lit by the blueish glow of lap- tops being watched on camp cots. Padding back from the show- ers, I’d pick my way past rows of fluorescent faces, featureless and blurred through the mosi-nets, each man absorbed in the snug little world of the nylon domes, somehow finding a privacy in the headphones and pretending to sleep through the telltale rhythmic rustling of the cot next door.

The frustration grew when the Inkerman Company, luckybastards (In Iraq they’d been my company), were crashed out in the middle of the night on a real-deal, this-is-not-a-drill, load-up-the-wagons tasking. As it turned out, they spent the next week bored and cold and with no sight of the enemy, but what was worrying was how selfishly and childishly jealous we all were. With nothing remotely gung-ho to boast of, we couldn’t even be bothered to write home, and moodily sat out at nights on the Hesco fence, watching the thunderstorms. Towering clouds hurling mag nificent bolts of lightning silhouetting the mountains to the north drifted over our heads as we sulked and, in the finest tradition of bored soldiers, sat around throwing stones at each other.

The days ticked by. The heat and dust grew more oppressive, and the reports from elsewhere in Helmand grew more exciting, and our own boredom intensified with each passing day we didn’t get out ‘on the ground’. Occasionally we would catch the whisper of something, the sniff of an American op going in to the north. But we were scheduled to spend the next two months training our kandak in camp. The idea of spending months trying to force Sandhurst on the ANA was unthinkable. Other companies started getting sent on real patrols and getting into real fights. Marlow was down on the Garmsir front line, and the daily SITREPs— situation reports sent back from the boys on the ground—were tantalizingly full of heavy engagements. The ANA soldiers, who had watched with amusement as we played our incomprehensible rugby sevens on the helipad, started to get bolshy, trying to play football right through our games. We were already telling our new comrades to piss off in their own country—as someone shouted from the wing: how the fuck was it ‘their’ helipad when their army had no helicopters?

They barely had an army.

________________________________________

205 Brigade of the 3rd (Hero) Corps of the Afghan National Army, though they didn’t know it and though certainly not enough of us knew it, were the solution to Afghanistan. We were trotting out the right phrases—‘An Afghan solution to an Afghan problem’— but we didn’t believe them. Back with the Operational Training and Advisory Group (OPTAG) on pre-deployment exercises in Norfolk, we had asked one of the instructors what special prepa- ration we should undertake to be an OMLT, and he had made a gag about eggs. It wasn’t OPTAG’s fault, not that the training they delivered wasn’t a waste of time. The problem was all in the name; ‘mentoring’ and ‘liaison’ sounded like holding hands and build- ing bridges. If we’d wanted to build bridges we’d have joined the Engineers; we were combat soldiers, a ‘teeth’ arm, and our culture demanded more. If they’d called the task OBFET (Operational Blow the Fuck out of Everything Team), then every battlegroup in the Army would have been creaming for it, but the Afghans might have objected.

Afghanistan was only going to work if the ANA could eventually do it for themselves. The Paras (Parachute Regiment), first out when the war began, had been thrust into a fight they couldn’t win on their own and forgot about the ANA in the midst of keeping the Taliban from their throats. The only story anyone heard about the ANA during the whole of the first British deployment into what the papers soon exclusively referred to as ‘the lawless Helmand Province’ was the one about how they ran away when Tim Illingworth of the Light Infantry won his Conspicuous Gallantry Cross. The Marines had come in six months later with a whole lot more people and, in theory, a whole lot more sense. They dedicated almost a whole Command...

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

- EditoreRiverhead Books

- Data di pubblicazione2010

- ISBN 10 1594484791

- ISBN 13 9781594484797

- RilegaturaCopertina flessibile

- Numero di pagine310

- Valutazione libreria

Compra nuovo

Scopri di più su questo articolo

Spese di spedizione:

GRATIS

In U.S.A.

I migliori risultati di ricerca su AbeBooks

The Junior Officers' Reading Club: Killing Time and Fighting Wars by Hennessey, Patrick [Paperback ]

Descrizione libro Soft Cover. Condizione: new. Codice articolo 9781594484797

The Junior Officers Reading Club Format: Paperback

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. Brand New. Codice articolo 1594484791

The Junior Officers' Reading Club: Killing Time and Fighting Wars

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. Book is in NEW condition. Codice articolo 1594484791-2-1

The Junior Officers' Reading Club: Killing Time and Fighting Wars

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Codice articolo 353-1594484791-new

The Junior Officers' Reading Club (Paperback)

Descrizione libro Paperback. Condizione: new. Paperback. Hailed as a classic of war writing in the U.K., The Junior Officers' Reading Club is a revelatory first-hand account of a young enlistee's profound coming of age. Attempting to stave off the tedium and pressures of army life in the Iraqi desert by losing themselves in the dusty paperbacks on the transit-camp bookshelves, Hennessey and a handful of his pals from military academy form the Junior Officers' Reading Club. By the time he reaches Afghanistan and the rest of the club are scattered across the Middle East, they are no longer cheerfully overconfident young recruits, hungering for action and glory. Hennessey captures how boys grow into men amid the frenetic, sometimes exhilarating violence, frequent boredom, and almost overwhelming responsibilities that frame a soldier's experience and the way we fight today.Watch a Video Hailed as a classic of war writing in the U.K., "The Junior Officers' ReadingClub" is a revelatory firsthand account of a young enlistee's profound comingof age. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Codice articolo 9781594484797

The Junior Officers Reading Club

Descrizione libro Condizione: New. pp. xv + 310, Maps. Codice articolo 261251000

The Junior Officers' Reading Club

Descrizione libro paperback. Condizione: New. Codice articolo 9781594484797

The Junior Officers' Reading Club: Killing Time and Fighting Wars

Descrizione libro Paperback. Condizione: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Codice articolo Holz_New_1594484791

The Junior Officers' Reading Club: Killing Time and Fighting Wars

Descrizione libro Paperback. Condizione: new. New. Codice articolo Wizard1594484791

The Junior Officers' Reading Club: Killing Time and Fighting Wars

Descrizione libro Paperback. Condizione: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Codice articolo think1594484791