jin chin yaotang fei kan jock (1 risultati)

Tipo di articolo

- Tutti gli articoli

- Libri (1)

- Riviste e Giornali

- Fumetti

- Spartiti

- Arte, Stampe e Poster

- Fotografie

- Mappe

-

Manoscritti e

Collezionismo cartaceo

Condizioni

- Tutte

- Nuovi

- Antichi o usati

Legatura

- Tutte

- Rilegato

- Brossura

Ulteriori caratteristiche

- Prima edizione

- Copia autografata

- Sovraccoperta

- Con foto

- No print on demand

Paese del venditore

Valutazione venditore

-

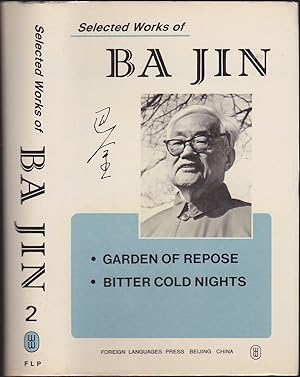

Selected Works of Ba Jin, Vol 2: Garden of Repose, Bitter Cold Nights

Editore: Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, 1988

ISBN 10: 7119005758ISBN 13: 9787119005751

Da: Books of the World, Arlington, VA, U.S.A.

Libro Prima edizione

Hardcover. Condizione: Fine. Condizione sovraccoperta: Fine. Huang Yinghao (illustratore). First Edition. Foreign Languages Press, 1988. Hardcover. First Edition (stated, actually First English-language Edition). Blue leatherette over boards with gold titles to spine and front board. Sewn binding. Sewn-in yellow silk place-marker. Fine book in a Fine jacket. Interior pristine. Spine straight and very tight. Light remainder mark to top edge. Very slight edge-wear to jacket. No tears. Not from a library. Not clipped. 502 pages. Garden of Repose (??, Qì Yuán, 1944) and Bitter Cold Nights (aka Cold Nights, ??, Hán Yè, 1947) are both critiques of China's traditional Confucian family system focusing on emotionally fragile and weak men struggling and failing to deal with family demands and social pressure. Both are set in Sichuan during the Sino-Japanese War (World War II) and both have been adapted into movies at least twice. Garden of Repose is the story of two decadent and decaying families. It follows the live of two characters: a drug addict from a rich family forced to sell his family home to a businessman, and the businessman's son, a spoiled and rude boy. The drug addict squats in an abandoned temple and is beaten to death in the streets; the boy falls down a garden well and drowns. Cold Nights portrays a Chinese Everyman?s slow death by tuberculosis; his consumption apparently caused less by the bacteria in his lungs than by the debilitative generational tensions of Republican China. The protagonist is torn between his traditional mother and his modern wife. With air raid alarms sounding through the cold winter nights, it is the arguments between mother and daughter-in-law in their small apartment that are the most corrosive and frustrating as relationships deteriorate in the social depression and ennui that pervade 1940s China. Ba Jin was the grand old man of Chinese literature from the heady years of the real cultural revolution in the 1920s and 1930s. Born into a large, wealthy Sichuanese clan, he was raised in a compound with as many as 100 relatives: the despotic grandfather, his two wives, all the adult sons and their wives and children, and eventually the grandchildren, plus dozens of servants. Family feuds broke out when Ba's grandfather died and authority was eventually transferred to an elder uncle. Ba Jin read widely and was deeply influenced by Piotr Kropotkin's famous pamphlet, "An Appeal to the Young." He called Emma Goldman his "spiritual mother" and engaged in a lifelong correspondence with her. After moving to Paris in his early 20s, he joined a group of young Chinese anarchists adopted the name Ba Jin: Ba from the first syllable in the surname of Mikhail Bakunin, and Jin for the last syllable of Kropotkin.