Articoli correlati a Cold Magic

Sinossi

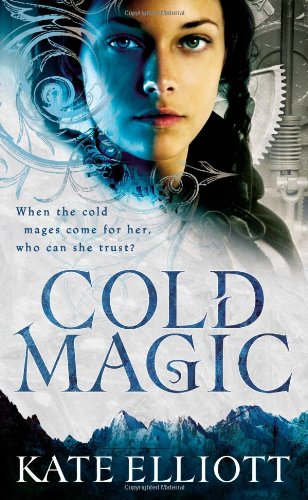

<b>From one of the genre's finest writers comes a bold new epic fantasy in which science and magic are locked in a deadly struggle.</b><br><br>It is the dawn of a new age. . . The Industrial Revolution has begun, factories are springing up across the country, and new technologies are transforming in the cities. But the old ways do not die easy.<br><br>Cat and Bee are part of this revolution. Young women at college, learning of the science that will shape their future and ignorant of the magics that rule their families. But all of that will change when the Cold Mages come for Cat. New dangers lurk around every corner and hidden threats menace her every move. If blood can't be trusted, who can you trust?

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

Informazioni sugli autori

<b>Kate Elliott</b> is the author of more than a dozen novels, including the Novels of the Jaran and, most recently, the Crossroads fantasy series. <i>King's Dragon</i>, the first novel in the Crown of Stars series, was a Nebula Award finalist; <i>The Golden Key</i> (with Melanie Rawn and Jennifer Roberson) was a World Fantasy Award finalist. Born in Oregon, she lives in Hawaii.

Kate Elliott is the author of more than a dozen novels, including the Novels of the Jaran and, most recently, the Crossroads fantasy series. King's Dragon, the first novel in the Crown of Stars series, was a Nebula Award finalist; The Golden Key (with Melanie Rawn and Jennifer Roberson) was a World Fantasy Award finalist. Born in Oregon, she lives in Hawaii. Find out more about the author at www.kateelliott.com or on twitter @KateElliottSFF.

Estratto. © Ristampato con autorizzazione. Tutti i diritti riservati.

Cold Magic

By Elliott, KateOrbit

Copyright © 2011 Elliott, KateAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780316080873

1

The history of the world begins in ice, and it will end in ice.

Or at least, that’s how the dawn chill felt in the bedchamber as I shrugged out from beneath the cozy feather comforter under which my cousin and I slept. I winced as I set my feet on the brutally cold wood floor. Any warmth from last evening’s fire was long gone. At this early hour, Cook would just be getting the kitchen’s stove going again, two floors below. But last night I had slipped a book out of my uncle’s parlor and brought it to read in my bedchamber by candlelight, even though we were expressly forbidden from doing so. He had even made us sign a little contract stating that we had permission to read my father’s journals and the other books in the parlor as long as we stayed in the parlor and did not waste expensive candlelight to do so. I had to put the book back before he noticed it was gone, or the cold would be the least of my troubles.

After all the years sharing a bed with my cousin Beatrice, I knew Bee was such a heavy sleeper that I could have jumped up and down on the bed without waking her. I had tried it more than once. So I left her behind and picked out suitable clothing from the wardrobe: fresh drawers, two layers of stockings, and a knee-length chemise over which I bound a fitted wool bodice. I fumblingly laced on two petticoats and a cutaway overskirt, blowing on my fingers to warm them, and over it buttoned a tight-fitting, hip-length jacket cut in last year’s fashionable style.

With my walking boots and the purloined book in hand, I cracked the door and ventured out onto the second-floor landing to listen. No noise came from my aunt and uncle’s chamber, and the little girls, in the nursery on the third floor above, were almost certainly still asleep. But the governess who slept upstairs with them would be rousing soon, and my uncle and his factotum were usually up before dawn. They were the ones I absolutely had to avoid.

I crept down to the first-floor landing and paused there, peering over the railing to survey the empty foyer on the ground floor below. Next to me, a rack of swords, the badge of the Hassi Barahal family tradition, lined the wall. Alongside the rack stood our house mirror, in whose reflection I could see both myself and the threads of magic knit through the house. Uncle and Aunt were important people in their own way. As local representatives of the far-flung Hassi Barahal clan, they discreetly bought and sold information, and in return might receive such luxuries as a cawl—a protective spell bound over the house by a drua—or door and window locks sealed by a blacksmith to keep out unwanted visitors.

I closed my eyes and listened down those threads of magic to trace the stirring of activity in the house: our man-of-all-work, Pompey, priming the pump in the garden; Cook and Aunt Tilly in the kitchen cracking eggs and wielding spoons as they began the day’s baking. A whiff of smoke tickled my nose. The tread of feet marked the approach of the maidservant, Callie, from the back. By the front door, she began sweeping the foyer. I stood perfectly still, as if I were part of the railing, and she did not look up as she swept back the way she had come until she was out of my sight.

Abruptly, my uncle coughed behind me.

I whirled, but there was no one there, just the empty passage and the stairs leading up to the bedchambers and attic beyond. Two closed doors led off the first-floor landing: one to the parlor and one to my uncle’s private office, where we girls were never allowed to set foot. I pressed my ear against the office door to make sure he was in his office and not in the parlor. My hand was beginning to ache from clutching my boots and the book so tightly.

“You have no appointment,” he said in his gruff voice, pitched low because of the early hour. “My factotum says he did not let you in by the back door.”

“I came in through the window, maester.” The voice was husky, as if scraped raw from illness. “My apologies for the intrusion, but my business is a delicate one. I am come from overseas. Indeed, I just arrived, on the airship from Expedition.”

“The airship! From Expedition!”

“You find it incredible, I’m sure. Ours is only the second successful transoceanic flight.”

“Incredible,” murmured Uncle.

Incredible? I thought. It was astounding. I shifted so as to hear better as Uncle went on.

“But you’ll find a mixed reception for such innovations here in Adurnam.”

“We know the risks. But that is not my personal business. I was given your name before I left Expedition. I was told we have a mutual interest in certain Iberian merchandise.”

Uncle’s voice got sharper without getting louder. “The war is over.”

“The war is never over.”

“Are you behind the current restlessness infecting the city’s populace? Poets declaim radical ideas on the street, and the prince dares not silence them. The common folk are like maddened wasps, buzzing, eager to sting.”

“I’ve nothing to do with any of that,” insisted the mysterious visitor. Too bad! I thought. “I was told you would be able to help me write a letter, in code.”

My heart raced, and I held my breath so as not to miss a word. Was I about to tumble onto a family secret that Bee and I were not yet old enough to be trusted with? But Uncle’s voice was clipped and disapproving, and his answer sadly prosaic.

“I do not write letters in code. Your sources are out of date. Also, I am legally obligated to stay well away from any Iberian merchandise of the kind you may wish to discuss.”

“Will you close your eyes when the rising light marks the dawn of a new world?”

Uncle’s exasperation was as sharp as a fire being extinguished by a blast of damp wind, but my curiosity was aflame. “Aren’t those the words being said by the radicals’ poet, the one who declaims every evening on Northgate Road? I say, we should fear the end of the orderly world we know. We should fear being swallowed by storm and flood until we are drowned in a watery abyss of our own making.”

“Spoken like a Phoenician,” said the visitor with a low laugh that made me pinch my lips together in anger.

“We are called Kena’ani, not Phoenician,” retorted my uncle stiffly.

“I will call you whatever you wish, if you will only aid me with what I need, as I was assured you could do.”

“I cannot. That is the end of it.”

The visitor sighed. “If you will not aid our cause out of loyalty, perhaps I can offer you money. I observe your threadbare furnishings and the lack of a fire in your hearth on this bitter-cold dawn. A man of your importance ought to be using fine beeswax rather than cheap tallow candles. Better yet, he ought to have a better design of oil lamp or even the new indoor gaslight to burn away the shadows of night. I have gold. I suspect you could use it to sweeten the trials of your daily life, in exchange for the information I need.”

I expected Uncle to lose his temper—he so often did—but he did not raise his voice. “I and my kin are bound by hands stronger than my own, by an unbreakable contract. I cannot help you. Please go, before you bring trouble to this house, where it is not wanted.”

“So be it. I’ll take my leave.”

The latch scraped on the back window that overlooked the narrow garden behind our house. Hinges creaked, for this time of year the window was never oiled or opened. An agile person could climb from the window out onto a stout limb to the wall; Bee and I had done it often enough. I heard the window thump closed.

Uncle said, “We’ll need those locks looked at by a blacksmith. I can’t imagine how anyone could have gotten that window open when we were promised no one but a cold mage could break the seal. Ei! Another expense, when we have little enough money for heat and light with winter blowing in. He spoke truly enough.”

I had not heard Factotum Evved until he spoke from the office, somewhere near Uncle. “Do you regret not being able to aid him, Jonatan?”

“What use are regrets? We do what we must.”

“So we do,” agreed Evved. “Best if I go make sure he actually leaves and doesn’t lurk around to break in and steal something later.”

His tread approached the door on which I had forgotten I was leaning. I bolted to the parlor door, opened it, and slipped inside, shutting the door quietly just as I heard the other door being opened. He walked on. He hadn’t heard or seen me.

It was one of my chief pleasures to contemplate the mysterious visitors who came and went and make up stories about them. Uncle’s business was the business of the Hassi Barahal clan. Still being underage, Bee and I were not privy to their secrets, although all adult Hassi Barahals who possessed a sound mind and body owed the family their service. All people are bound by ties and obligations, and the most binding ties of all are those between kin. That was why I kept stealing books out of the parlor and returning them. For the only books I ever took were my father’s journals. Didn’t I have some right to them, being that they, and I, were all that remained of him?

Feeling my way by touch, I set my boots by a chair and placed the journal on the big table. Then I crept to the bow window to haul aside the heavy winter curtains so I would have light. All eight mending baskets were set neatly in a row on the narrow side table, for the women of the house—Aunt Tilly, me, Beatrice, her little sisters, our governess, Cook, and Callie—would sit in the parlor in the evening and sew while Uncle or Evved read aloud from a book and Pompey trimmed the candle wicks. But it was the bound book of slate tablets resting beneath my mending basket that drew my horrified gaze. How had I forgotten that? I had an essay due today for my academy college seminar on history, and I hadn’t yet finished it.

Last night, I had tucked fingerless writing gloves and a slate pencil on top of my mending basket. I drew on the gloves and pulled the bound tablets out from under the basket. With a sigh, I sat down at the big table with the slate pencil in my left hand. But as I began reading back through the words to find my place, my mind leaped back to the conversation I had just overheard. The rising light marks the dawn of a new world, the visitor had said; or the end of the orderly world we know, my uncle had retorted.

I shivered in the cold room. The war is never over. That had sounded ominous, but such words did not surprise me: Europa had fractured into multiple principalities, territories, lordships, and city-states after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the year 1000 and had stayed that way for the last eight hundred years and more; there was always a little war or border incident somewhere. But worlds do not begin and end in the steady mud of daily life, even if that mud involves too many petty wars, cattle raids, duels, feuds, legal suits, and shaky alliances for even a scholar to remember. I could not help but think the two men were speaking in a deeper code, wreathed in secrets. I was sure that somewhere out there lay hidden the story of what we are not meant to know.

The history of the world begins in ice, and it will end in ice. So sing the Celtic bards and Mande djeliw of the north whose songs tell us where we came from and what ties and obligations bind us. The Roman historians, on the other hand, claimed that fire erupting from beneath the bones of the earth formed us and will consume us in the end, but who can trust what the Romans say? Everything they said was used to justify their desire to make war and conquer other people who were doing nothing but minding their own business. The scribes of my own Kena’ani people, named Phoenicians by the lying Romans, wrote that in the beginning existed water without limit, boundless and still. When currents stirred the waters, they birthed conflict and out of conflict the world was created. What will come at the end, the ancient sages added, cannot be known even by the gods.

The rising light marks the dawn of a new world. I’d heard those words before. The Northgate Poet used the phrase as part of his nightly declamation when he railed against princes and lords and rich men who misused their rank and wealth for selfish purposes. But I had recently read a similar phrase in my father’s journals. Not the one I’d taken out last night. I’d sneaked that one upstairs because I had wanted to reread an amusing story he’d told about encountering a saber-toothed cat in a hat shop. Somewhere in his journals, my father had recounted a story about the world’s beginning, or about something that had happened “at the dawn of the world.” And there was light. Or was it lightning?

I rose and went to the bookshelves that filled one wall of the parlor: my uncle’s precious collection. My father’s journals held pride of place at the center. I drew my fingers along the numbered volumes until I reached the one I wanted. The big bow window had a window seat furnished with a long plush seat cushion, and I settled there with my back padded by the thick winter curtain I’d opened. No fire crackled in the circulating stove set into the hearth, as it did after supper when we sewed. The chill air breathed through the paned windows. I pulled the curtains around my body for warmth and angled the book so the page caught what there was of cloud-shrouded light on an October morning promising yet another freezing day.

In the end I always came back to my father’s journals. Except for the locket I wore around my neck, they were all I had left of him and my mother. When I read the words he had written long ago, it was as if he were speaking to me, in his cheerful voice that was now only a faint memory from my earliest years.

Here, little cat, I’ve found a story for you, he would say as I snuggled into his lap, squirming with anticipation. Keep your lips sealed. Keep your ears open. Sit very, very still so no one will see you. It will be like you’re not here but in another place, a place very far away that’s a secret between you and me and your mama. Here we go!

2

Once upon a time, a young woman hurried along a rocky coastal path through a fading afternoon. She had been sent by her mother to bring a pail of goat’s milk to her ailing aunt. But winter’s tide approached. The end of day would usher in Hallows Night, and everyone knew the worst thing in the world was to walk abroad after sunset on Hallows Night, when the souls of those doomed to die in the coming year would be gathered in for the harvest.

But when she scaled the headland of Passage Point, the sun’s long glimmer across the ice sea stopped her in her tracks. The precise angle of that beacon’s cold fire turned the surface of the northern waters into glass, and she saw an uncanny sight. A drowned land stretched beneath the waves: a forest of trees; a road paved of fitted stone; and a round enclosure, its walls built of white stone shimmering within the deep and pierced by four massive gates hewn of ivory, pearl, jade, and bone. The curling ribbons rippling along its contours were not currents of tidal water but banners sewn of silver and gold.

So does the spirit world enchant the unwary and lead them onto its perilous paths.

Too late for her, the land of the ancestors came alive as the sun died beyond the western plain, a scythe of light that flashed and vanished. Night fell.

As a full moon swelled above the horizon, a horn’s cry filled the air with a roll like thunder. She looked back: Shadows fled across the land, shapes scrambling and falling and rising and plunging forward in desperate haste. In their wake, driving them, rode three horsemen, cloaks billowing like smoke.

The masters of the hunt were three, their heads concealed beneath voluminous hoods. The first held a bow made of human bone, the second held a spear whose blade was blue ice, and the third held a sword whose steel was so bright and sharp that to look upon it hurt her eyes. Although the shadows fleeing before them tried to dodge back, to return the way they had come, none could escape the hunt, just as no one can escape death.

The first of the shadows reached the headland and spilled over the cliff, running across the air as on solid earth down into the drowned land. Yet one shadow, in the form of a lass, broke away from the others and sank down beside her.

“Lady, show mercy to me. Let me drink of your milk.”

The lass was thin and trembling, more shade than substance, and it was impossible to refuse her pathetic cry. She held out the pail of milk. The girl dipped in a hand and greedily slurped white milk out of a cupped palm.

And she changed.

She became firm and whole and hale, and she wept and whispered thanks, and then she turned and ran back into the dark land, and either the horsemen did not see her or they let her pass. More came, struggling against the tide of shadows: a laughing child, an old man, a stout young fellow, a swollen-bellied toddler on scrawny legs. Those who reached her drank, and they did not pass into the bright land of the ancestors. They returned to the night that shrouded the land of the living.

Yet, even though she stood fast against the howl of the wind of foreordained death, few of the hunted reached her. Fear lashed the shadows, and as the horsemen neared, the stream of hunted thickened into a boiling rush that deafened her before it abruptly gave way to a terrible silence. A woman wearing the face her aunt might have possessed many years ago crawled up last of all and clung to the rim of the pail, too weak to rise.

“Lady,” she whispered, and could not speak more.

“Drink.” She tipped the pail to spill its last drops between the shade’s parted lips.

The woman with the face of her aunt turned up her head and lifted her hands, and then it seemed she simply sank into the rock and vanished. A sharp, hot presence clattered up. The spearman and the bowman rode on past the young woman, down into the drowned land, but the rider with the glittering sword reined in his horse and dismounted before she could think to run.

The blade shone so cold and deadly that she understood it could sever the spirit from the body with the merest cut. He stopped in front of her and threw back the hood of his cloak. His face was black and his eyes were black, and his black hair hung past his shoulders and was twisted into many small locks like the many cords of fate that bind the thread of human lives.

She braced herself. She had defied the hunt, and so, certainly, she would now die beneath his blade.

“Do you not recognize me?” he asked in surprise.

His words astonished her into speech. “I have never before met you.”

“But you did,” he said, “at the world’s beginning, when our spirit was cleaved from one whole into two halves. Maybe this will remind you.”

His kiss was lightning, a storm that engulfed her.

Then he released her.

What she had thought was a cloak woven of wool now appeared in her sight as a mantle of translucent power whose aura was chased with the glint of ice. He was beautiful, and she was young and not immune to the power of beauty.

“Who are you?” she asked boldly.

And he slowly smiled, and he said—

“Cat!”

My cousin Beatrice exploded into the parlor in a storm of coats, caps, and umbrellas, one of which escaped her grip and plummeted to the floor, from whence she kicked it impatiently toward me.

“Get your nose out of that book! We’ve got to run right now or you’ll be late!”

I ripped my besotted gaze from the neat cursive and looked up with my most potent glower.

“Cat! You’re blushing! What on earth are you reading?” She dumped the gear on the table, right on top of the slate tablets.

“Ah! That’s my essay!”

With a fencer’s grace and speed, Bee snatched the journal out of my hands. Her gaze scanned the writing, a fair hand whose consistent and careful shape made it easy to read from any angle.

She intoned, in impassioned accents, “ ‘His kiss was lightning, a storm that engulfed her’! If I’d known there was romance in Uncle Daniel’s journals, I would have read them.”

“If you could read!”

“A weak rejoinder! Not up to your usual standard. I fear reading such scorching melodrama has melted your cerebellum.”

“It’s not melodrama. It’s an old traditional tale—”

“Listen to this!” She slapped a palm against her ample bosom and drawled out the words lugubriously. “ ‘And he slowly smiled, and… he… said—’ ”

“Give me that!” I lunged up, grabbing for the journal.

She skipped back, holding it out of my reach. “No time for kisses! Get your coat on. Anyway, I thought your essay was…” She excavated the tablets, flipped them closed, and squinted her eyes to consider the handsomely written title. “Blessed Tanit, protect us!” she muttered as her brows drew down. She made a face and spoke the words as if she could not believe she was reading them. “ ‘Concerning the Mande Peoples of Western Africa Who Were Forced by Cold Necessity to Abandon Their Homeland and Settle in Europa Just South of the Ice Shelf.’ Could you have made that title longer, perhaps? Anyway, what do kisses have to do with the West African diaspora?”

“Nothing. Obviously!” I sat on a chair and began to lace up my boots. “I was thinking of something else. The beginning and ending of the world, if you must know.”

She wrinkled her nose, as at a bad smell. “The end of the world sounds so dreary. And so final.”

“And I remembered that my father mentioned the beginning of the world in one of his journals. But this was the wrong story, even though it does mention ‘the world’s beginning.’ ”

“Even I could tell that.” She glanced at the page. “ ‘When our spirit was cleaved from one whole into two halves.’ That sounds painful!”

“Bee! The entire house can hear you. We’re not supposed to be in here.”

“I’m not that loud! Anyway, of course I spied out the land first. Mother and Shiffa are up in the nursery where Astraea is having a tantrum. Hanan is on the landing, keeping watch. Father and Evved went all the way out into the back. So we’re safe, as long as you hurry!”

I plucked the journal from her hand and set it on the table. “You go on ahead to the academy. I just need to write a conclusion. It’s the seminar the headmaster teaches, and I hate to disappoint him. He never says anything. He just looks at me.” I excavated my slate tablet and pencil from beneath the coats and caps.

Bee shoved my coat onto one of the chairs, searching for her cap. After tying it tight under her chin and pulling on her coat, she swung her much-patched cloak over all. “Don’t be late or Father will forbid us the trip to the Rail Yard.”

“Which handsome pupil do you intend to flirt with there?”

She launched a glare like musket shot in my direction and strode imperiously from the parlor, not bothering to answer. I wrote my conclusion. Her little sister Hanan clattered down the stairs with her to bid her farewell by the front door. Up in the nursery, Astraea had launched into one of her mulish fits of “no no no no no,” and our governess, Shiffa, had reverted to her most coaxing voice to appease her. Aunt Tilly’s light footsteps passed down the steps to the ground floor and thence back to the kitchen, no doubt to consult with Cook about finding something sweet to break the little brat’s concentration. I wrote hurriedly, not in my best script and not with my most nuanced understanding.

That is how those druas with secret power among the local Celtic tribes, and the Mande refugees with their gold and their hidden knowledge, came together and formed the mage Houses. The power of the Houses allowed them to challenge princely rule while—

I heard footsteps coming up the stairs, and a key turned in the office door. I paused, hand poised above the slate. Men entered the office; the door was shut.

Uncle spoke in a low voice no one but me could have heard through the wall. “You were supposed to come at midnight.”

A male voice answered. “I was delayed. Is everything here I paid for?”

“Here are the papers.”

“Where is the book?”

“Melqart’s Curse! Evved, didn’t you get the book?”

“It must still be in the parlor. Just a moment.”

I wiped the “while” from the slate and pressed a hasty, smeared period to the sentence. It would have to do. I scooped up the slate tablet and my schoolbag, bolted for the door, and got out just as the door between the study and the parlor was unlocked.

I halted on the landing to listen. Aunt Tilly was back upstairs, speaking with Shiffa about the girls’ lessons for the day while Astraea whined, “But I wanted yam pudding, not this!” Meanwhile, Hanan had gone back to the kitchen and was chattering with Cook and Callie in her high, sweet voice as the three began to peel turnips. Pompey, with his distinctive uneven tread, was in the basement. I fled down the main stairs and out the front door, and it was not until I was out of sight of the house that I realized I had forgotten my coat, cap, and umbrella. I dared not return to fetch them.

Yet what is cold, after all, but the temperature to which we are most accustomed? It is cold for half the year here in the north. However pleasant the summer may seem, the ice never truly rests; it only dozes through the long days of Maius, Junius, Julius, and Augustus with its eyes half closed. I stuffed the tablet in my schoolbag between a new schoolbook and my scholar’s robe, and kept going. To keep warm, I ran instead of walking, all the way through our modest neighborhood and then up the long hill into the old temple district where the new academy had been built twenty years ago. Fortunately, the latest fashionable styles allowed plenty of freedom for my legs and lungs.

As I crossed under the gates into the main courtyard, a fine carriage pulled up to disgorge a brother and two sisters swathed in fur-lined cloaks. Though late like me, they were so rich and well connected that they could walk right in the front through the grand entry hall without fearing censure, while I fumbled with frozen hands at the servants’ entrance next to the latrines. The cursed latch was stuck.

“Salve, Maestressa Barahal. May I help you with that?”

I swallowed a yelp of surprise and looked up into the handsome face of Maester Amadou Barry, who had evidently followed me to the side door. His sisters were nowhere in sight.

“Salve, maester,” I said prettily. “I saw you and your sisters arrive.”

“You’re not dressed for the weather,” he remarked, pushing on the latch until it made a clunk and opened.

“My things are inside,” I lied. “I can’t be late, for the proctor locks the balcony door when the lecture starts.”

“My apologies. I was just wondering if your cousin Beatrice…” His pause was so awkward that I smiled. I was certain he was blushing. “And you, of course, and your family, intend to visit the Rail Yard when it is open for viewing next week.”

“My uncle and aunt intend to take Beatrice and me, yes,” I replied, biting down another smile. “If you’ll excuse me, maester.”

“My apologies, for I did not mean to keep you,” he said, backing away, for a young man of his rank would certainly enter through the front doors no matter how late he was.

Inside, as I raced along a back corridor, all lay quiet except for a buzz of conversation from the lecture hall. I had a chance to get to my seat before it was too late. In icy darkness, I hurried up the narrow steps that led to the balcony of the lecture hall. The proctor had already turned off the single gaslight that lit the stairwell and had gone in, but I knew these steps well. With the strap of my schoolbag gripped between my teeth, I tugged my scholar’s robe on over my jacket and petticoats. I shrugged the satin robe up over both shoulders and smoothed it down just as I felt the change of temperature, from bone cold to merely flesh-achingly chilly, that meant the door loomed ahead.

Had the proctor locked it already?

Blessed Tanit! Watch over your faithful daughter. Let me not be late and get into trouble. Again.

3

My hand tightened on the iron latch, the metal so cold it burned through the palm of my writing gloves. I applied pressure, and the latch clicked blessedly free. Catching my breath, I listened as female voices gossiped and giggled, schoolbook pages turned, and pencil leads scratched on paper. A heavy tread approached, accompanied by the jangle of a ring of keys. Straightening, I opened the door and crossed the threshold into the proctor’s basilisk glare.

She lowered the key she had been about to insert into the lock and attempted to wither me with a sarcastic smile. “Maestressa Catherine Hassi Barahal. How gracious of you to attend today’s required lecture.”

I opened my mouth to offer a clever reply, but I had forgotten the schoolbag gripped between my teeth and had to grab for it as it fell. The neat catch allowed me to sweep into a courtesy. “Maestra Madrahat. Forgive me. I was discommoded.”

Some things you could not fault a respectable young woman for in public, even if you wondered if she was telling the truth. She favored me with a raised eyebrow eloquent of doubt but stepped aside so I could squeeze past her along the back aisle toward my assigned bench. “Button your robe, maestressa,” she added, her parting shot.

As I hastened along the aisle, shaking from relief and shivering from the cold, I heard her key turn in the lock. Once again, I had landed—just barely—on my feet.

A few of the other pupils glanced my way, but I wasn’t important enough to be worth more than a titter, an elbow nudge, or a yawn. At the back of the balcony’s curve, I slipped onto the bench beside Beatrice. Her schoolbook was open to a page half filled in with an intricate drawing, and she was shaking a broken lead out of her pencil as I sat down.

“There you are!” she whispered without looking at me, intent on her pencil lead. “I knew you would make it here in time.”

“Your confidence heartens me.”

“I dreamed it last night.” She slanted a sidelong look at me. “You know I always believe my dreams.”

Below, on the dais at the front of the lecture hall, two servants rolled out a chalkboard and hung a net filled with sticks of chalk from its lower rim.

I bent closer. “I thought you dreamed only about certain male students—”

She kicked me in the ankle.

“Ouch!”

The headmaster limped out onto the dais and we fell silent, as did every other pupil, males below on the main floor and females above on the balcony. The old scholar was not one to drag out an introduction: a name, a list of spectacular experiments accomplished and revolutionary papers published, and the title of the lecture we were privileged to hear today: Aerostatics, the principles of gases in equilibrium and of the equilibrium of balloons and dirigible balloons in changing atmospheric conditions. Then he was finished, although a surprised murmur swept the hall as the students realized the lecturer was a woman.

“So, did you complete the essay?” Bee demanded, the words barely voiced but her expression emphatic. “I know how you love the headmaster’s seminar. It would be awful if you couldn’t go.”

Under cover of the measured entrance of the dignitary in a headwrap and crisply starched and voluminous orange boubou, I made a business of extricating my schoolbook from my bag and arranging it neatly open before me on the pitted old table with my new silver pencil set diagonally across the blank page. Meanwhile, I spoke fast in a low voice as Bee fiddled with her broken lead.

“I finished but not quite how I wanted it. It was the strangest thing. Some man had come in through the window and was waiting in the study.”

“How did he manage that?”

“I don’t know. Uncle wondered the same thing. That’s why they’d gone out to the garden when you came down. Then another man came after that. Uncle had to get a book from the parlor for him—I had to run so Evved wouldn’t see me. Blessed Tanit! I left the journal I was reading on the table. He’ll wonder why it was there!”

“He’s been very absentminded and more snappish than usual these days. I think he’s anxious about something. Something he and Mama aren’t telling us. So perhaps he won’t notice or will forget to ask.”

“I hope so. What else could I do? I grabbed my schoolbag and my essay, and I ran all the way to the academy, only I forgot my coat, so I was very, very cold.” I was still cold, because a third of the long underceiling windows were propped open with sticks to move air through the otherwise stuffy confines of the cramped balcony tiers. “One exciting thing did happen, however,” I added coyly. “As I ran into the courtyard, a very fine carriage rolled up and who should step out but Maester Amadou and his twin sisters.”

Bee’s hands stilled. Her rosy lips pressed tight. She did not rise to the bait. Not yet, but she would. Instead, she said in the most casual voice imaginable, “I saw the twins come in.” She gestured to a pair of girls seated in the front row by the balcony railing, resplendent in gold-and-blue robes cut to emphasize their tall figures, their hair wrapped in waxed cotton scarves whose sheen might have given off more light than the poor gas illumination. They recorded dutiful notes, writing in unison, as the esteemed professor sketched the lines of an airship on the chalkboard. “How did they get up here faster than you did?”

I smiled, luring her closer. “Maester Amadou stopped me. To ask a question.”

“Oh. A question.” She sighed wearily, as if his questions were the most uninteresting thing in the world to her.

“He asked about you.”

Sprung! I gloated expectantly, but she turned her back on me, her attention flying away to fix on a spill of movement in the hall below us. Certain male pupils were coming in fashionably late and now settled into their assigned places. It seemed likely she would stare at Maester Amadou’s attractive form and excellent clothes for the next century just to thwart me of the chance to annoy her, or perhaps she would stare at him because she had been doing so from the first day he and his sisters had arrived as pupils at the academy college, right after the Beltane festival day almost six months ago at the beginning of the month of Maius.

Two could move pieces in that chess game.

I rearranged my skirts, careful to fold back the front cut of the outer skirt so as to reveal the inner layers of petticoats, and tugged on my jacket to make sure it fit properly down around my hips. Then I buttoned the academic robe to conceal it all and folded my hands in my lap.

I tried to listen as the distinguished guest lecturer abandoned the introductory remarks to begin devouring the meat of the talk—the principles of aerostatic aircraft popularly known as airships and balloons. An interesting topic, especially in a time when the new technological innovations were very controversial. It was particularly interesting because the scholar was female and from the south, from the famous Academy of Natural Science and History in Massilia, on the Mediterranean, where female students were, so it was rumored, allowed to sit on the same benches as male students.

Because I had run from our house to the academy, a significant distance and much of it uphill, and because of my late essay, I hadn’t had time to eat my morning porridge. So now, despite the unpadded bench pressing uncomfortably into my backside and the chilly draft wrapping my shoulders, I began to doze off.

A body immersed in a fluid is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the displaced fluid. Likewise, by this same principle, a craft that is lighter than air will be buoyant… gases expand in volume with a rise in temperature… by creating a cavity filled with flammable air… if pigs could fly, where would they go?… Will there be yam pudding for luncheon?…

I am sailing across a blinding expanse of ice in a schooner that skates the surface of a massive ice sheet, and a personage stands beside me who I know is my father even though, as happens in dreams, he looks nothing like the man whose portrait I wear in a locket at my neck—

A jab to my ribs brought me to my senses. I jerked awake, grabbing for my pencil, but it wasn’t lying on my open schoolbook where I had left it. Bee’s right hand gripped my right wrist and pinned my hand to the table we shared. Idly, I noted the smeared gray of pencil lead on the tips of her thin white wool gloves.

“What did he ask about me?” she whispered. Under the gloomy hiss of the gaslights—we female pupils stuck up here in the balcony got only half the light afforded the male pupils in the main hall below—I could see her flutter her eyelashes in that obnoxious way she had, the one that never failed to demolish the objections and reproaches of any adult caught in the beat of those dark wings. “Cat,” she added, her voice warming, “you have to tell me.”

I yawned to annoy her. “I’m bound by a contract not to tell.”

She released my wrist and punched me on the shoulder.

“Ouch!”

Heads turned. Though she might look like a dainty little thing, Bee was a bruiser, really pitiless when she got roused. I glanced toward the curtained entrance where the proctor stood at guard as stiff as a statue and as grim as winter, staring straight ahead. The industrious pupils returned their attention to the lecture, and the bored slumped back to their naps.

“You earned it!” Bee knew precisely how to pitch her voice so only I could hear her. “I’ve been in love with him forever.”

“Three weeks!” I rubbed my shoulder.

“Three months! Ever since I had that dream of him standing, sword drawn, on earthen ramparts while fending off soldiers wearing the livery of a mage House.” She pressed a hand to her chest, which was heaving under a high-collared dress appropriate for the academy college’s proper halls. “I have kept the truth of my desperate feelings to myself for fear—”

“For fear we’d wonder why you so suddenly left off being in love with and destined to wed Maester Lewis of the lovely red-gold hair and turned your tenacious heart to the beauty of Maester Amadou with his piercing black eyes.”

“Which you yourself admit are handsome.”

She bent forward to look over the rows of benches and the female pupils seated in pairs at study tables. Given that we were seated in the cramped back row of benches with the other female scholarship students, we could see only the front third of the spacious main hall below us. Maester Amadou lounged in the second row in a chair placed at a polished table close to the podium. His fashionably clothed back was to us, but I could see that he was rolling dice with his tablemate, the equally well-connected Maester Lewis, a youth of high rank who had been fostered out to the court of the ruling prince of Tarrant whose territory included our city of Adurnam. The young men were both so strikingly good-looking that I wondered if they sat together the better to display their contrasting appearances, one milk white and gold haired and the other coffee dark and black haired. On the dais, pacing back and forth in front of the chalkboard and waving a hand in enthusiastic measure, the esteemed natural philosopher launched into an explosive digression on the natural laws pertaining to the behavior of gases, words scattering everywhere.

“Yes, he’s almost as pretty as you are,” I retorted, “and well aware that his family’s wealth allows him to walk in late and then to game in the front of the hall, all without repercussion. He’s the vainest young man I ever met.”

“How can you say so? The story of how he and his three sisters and aunt escaped from the assault on Eko by murderous, plague-ridden ghouls—forced to call their good-byes to their parents and cousins left behind on the shore as the monsters advanced. It’s a heartbreaking tale!”

“If it’s true. The settlement and fort were specifically established at Eko because it is an island, and ghouls can’t cross water. So how could ghouls have reached them? Anyone can say what they like when there are no witnesses.”

“You just have no heart, Cat. You’re heartless.” Her scowl was meant to pierce me to the heart, if I’d had one. With an indignant flounce of the shoulders, she turned away to furiously sketch on a blank page of her book, using my good silver pencil with its fresh lead.

“If by that you mean I don’t fall head over ears in love with every handsome face I encounter, then I thank the blessed Tanit for it! Someone needs to be heartless. His family is well-to-do and well connected, that’s certain. His elder sister married the younger brother of the cousin of the Prince of Tarrant. His aunt is known to be very clever at business, with contacts reaching across the banking houses of the south. All points in his favor. Especially given the always impoverished state of the Barahal finances. Now I want my pencil back.”

“You’re going to tell me what he asked about me,” she murmured without looking up or ceasing her drawing, “because otherwise I will pour a handful of salt into your porridge every morning for the next month—”

“Catherine! Beatrice! The Hassi Barahal cousins are again demonstrating their studiousness, I comprehend.”

Distracted by the sound of Beatrice’s voice, I hadn’t noticed the proctor’s slithering approach along the back aisle. She came to rest right behind us, close enough that her breath stirred the hair on my neck. Her gaze swept the balcony. The other female pupils were all intent on recording the formula V(1)T(2) = V(2)T(1), which was shedding chalk dust on the board as the venerable professor repeated Alexandre’s law: At constant pressure, the volume of a given mass of an ideal gas increases or decreases by the same factor as its temperature increases or decreases.

The maestra grabbed my schoolbook off the table and flipped through its blank pages. “Is this a new schoolbook, maestressa? Or the sum total of your knowledge?”

Cats always land on their feet. “Flammable air is fourteen times lighter than life-sustaining air. It can be produced by dissolving metals in acid. Gas expands as its temperature goes up. No wonder the mage Houses hate balloons! If it’s true that proximity to a cold mage always decreases the ambient temperature of any object, then wouldn’t a cold mage deflate any balloon sack just by standing alongside it?”

Her narrowed gaze would have flattened an elephant. But the gods were merciful, because instead of sending me off to the headmaster’s office for impertinence, she turned her attention to Bee. My dearest and most beloved cousin hastily set down my pencil and attempted to close her sketchbook. The proctor slapped a hand down, holding it open to the page where Bee had just sketched an impressive portrait of a personage obviously meant to be me. With a cackling death’s-head grimace and denarii for eyes, the caricature gazed upon an object held out before it in a bony hand.

“I see you have been paying attention in anatomy, at least,” remarked the maestra as icily as the draft that shivered over us through the high window slits. “That is a remarkably good likeness of a four-chambered heart, although is a heart not meant to reside in the chest cavity?”

Bee batted her eyelashes as her honey smile lit her face. “It was a moment’s fancy, that is all. An allegory in the Greek style, if you will. If you look at the other pages, you’ll see I have been most assiduously attending to this recent series of lectures on the principles of balloon and airship design.” She kept talking as she flipped through the pages. The babble pouring mellifluously from her perfect lips began to melt Maestra Madrahat’s rigid countenance. Buoyed up by a force equal to… gases expand in volume wit?…

Soon pigs would fly.

“Such fine draftsmanship,” the proctor murmured besottedly as Bee displayed page after page of air sacs inflated and deflated and hedged about with all manner of mathematical formulae and proportional notations, balloons rising and slumping according to temperature and pressure, hapless passengers being tossed overboard from baskets on high and falling with exaggerated screams and outflung arms—

The maestra stiffened, breath sucked in hard.

Bee swiftly turned to a more palatable historical sketch of the Romans kneeling in defeat at Zama before the newly crowned queen, the dido of our people, and her victorious general Hanniba’al. And she kept talking. “I am so very deeply anticipating our outing to the Rail Yard next week, where we will be able to view the airship for ourselves. How incredible that it propelled itself all the way across the Atlantic Ocean from Expedition to our fair city of Adurnam! Not a single human or troll lost in the crossing!”

“Imagine,” I added, unable to control my tongue, “how the cold mages must be celebrating its arrival, considering that the mage Houses call airships and rifles the reckless tinkering of radicals who mean to destroy society. Do you suppose the mages mean to join the festivities next week as well? It’s said half the city means to turn out to see the airship, if only to stop the Houses from attempting something rash.”

Every pupil sitting near enough to overhear my words gasped. Hate the Houses if you wished, or kneel before them hoping to be offered a trickle from the bounteous stream of their power and riches and influence, but everyone knew it was foolish to openly speak critical words. Even the lords and princes who ruled the many principalities and territories of fractious Europa did not challenge the Houses and their magisters.

The proctor snatched Bee’s book from the table and tucked it under an arm. “The headmaster will see you both in his office after class.”

Half the girls on the balcony snickered. The other half shuddered. The twins kept taking notes, although I didn’t know them well enough to say if they were that oblivious or that focused. Maestra Madrahat took up her guard post at the entrance, her keys hanging in plain sight to remind us that no one could sneak out and down the stairs and that no venturesome young male could sneak up and in. None of that here, in the abstemious halls of the academy.

The headmaster will see you both.

“Oh, Cat, what have we done now?” Our hands clasped as we shivered in a sudden cold wind coursing like a presentiment of disaster down from the high windows.

Bee and Cat, together forever. No matter what trouble we got into, we would, as always, face it as one.

4

When the lecture ended, we all dutifully snapped fingers and thumbs to show approval. Afterward, some students stood to offer praise, one male pupil raising a song while a chorus, scattered through the hall and balcony, clapped a rhythm and sang the response:

To the maestra of learning, heavy with wisdom.

On this day we greet you.

Our ears like maize grow ripe with knowledge.

On this day we greet you.

Bee hummed and tapped along, offbeat and out of tune. The academy’s head of natural history offered a mercifully brief speech thanking the eminent visitor for gracing us with her presence and illuminating insights, and afterward reminded the gathered pupils of the academy-sponsored trip to the Rail Yard to view the airship, coming up next week, and the public lecture to be offered on this very evening by the very same visiting scholar on the very same subject.

Bee sighed as she returned my pencil. “Father will make us go. It’s hopeless. We’re doomed to the dreary gray of Sheol for another evening of hearing the same lecture all over again.”

“I thought you’d given up believing in the afterlife after last year’s lecture series on natural philosophy.”

“Reason is the measure of all things. It’s perfectly reasonable to assume I will die of boredom if I have to sit through the same lecture all over again.”

“You just said that.”

“Exactly my point. I won’t even be allowed to draw.”

“Say you have a headache.”

“That was my excuse last week when the eminent scholar from the academy in Havery was speaking on the origin, nature, range, function, and persistence of ice sheets.”

“That one was actually interesting. Did you know that glacial ice covers all land north of fifty-five degrees latitude and once covered the land as far south as Adurnam—”

“Quiet!” She dropped her head into her hands, strands of black hair curling around her fingers. Her elegant silver blessing bracelet, given to her by her mother seven years ago when she made twelve, glimmered like a dido’s precious keepsake in the amber light. “I’m devising a desperate scheme.”

I slipped my schoolbook into my bag beside the essay and buttoned the pencil into its pocket, from which Bee could not easily steal it. We waited for the balcony to clear: The back-row students always descended last. When our turn came, we rose in order and filed out past Maestra Madrahat. The proctor still clutched Bee’s sketchbook, and I wondered if Bee would snatch it out of her hands, but the fateful moment passed as we pushed into the narrow stairwell, following the other whispering girls down the steep steps while the last of the row clipped at our heels. The gaslight’s flame murmured.

The young woman ahead of us turned her head to address Bee, who was in front of me. “Was that the book with the naughty drawings?” she asked.

“Yes.” Bee’s whisper hissed up and down the stairwell, and other girls fell silent to listen. “Ten pages drawn after the lecture on the wicked rites of sacred prostitution practiced in the ancient Phoenician city of Tyre according to the worship of the goddess Astarte.”

More giggling. I rolled my eyes.

“Those are just lies the Romans told,” said our interlocutor, who, like us, was the daughter of an old and impoverished Kena’ani lineage. Unlike us, Maestressa Asilita had been given a place at the academy college because of her genuine scholarly attainments. In addition, she had a remarkable gift for coaxing Bee off the cliff. “Like the ones about child sacrifice. Do you have drawings of that, too?”

“Bee,” I warned.

“Grieving parents wailing as they scratch their own faces and arms to draw blood? Priests cutting the throats of helpless infants and lopping off their tiny heads? And then casting their plump little bodies into the fire burning within the arms of the Lord of Ba’al Hammon? Of course!”

Girls shrieked while others, sad to say, giggled even more.

“What is that you said, Maestressa Hassi Barahal?” demanded the proctor’s voice from on high.

“I said nothing, maestra,” I called back as I ground a fist into Bee’s back. “I spoke my cousin’s name only because I was tripping on her hem and I wanted her to move faster.”

The light at the end of the stairs beckoned. We surged out and down the wide corridor in a chattering mass of young women soon joined by a chattering mass of young men. The actual children, the pupils under sixteen, were herded away to the school building in the back of the academy, but we college pupils spilled into the high entrance hall to await the summons to luncheon.

The academy had been erected only two decades before with funds raised from well-to-do families who resided in the prosperous city of Adurnam and its neighboring countryside, all ruled over by the Prince of Tarrant and his clan. Those families came from many different backgrounds, and some had fought bitter wars or engaged in blood feuds in the past. The prince had clearly instructed the architect to placate everyone and offend no one. Therefore, the inner stone facade of the entrance hall had been carved with a series of reliefs depicting plants: princely white yams, hardy kale, broom millet, poor-man’s chestnut, jolly barley, honest spelt, humble oats, winter rye, broad beans, northern peas, sweet pears and apples, stolid turnip, quick radish, and even the newcomers brought over the ocean—maize and potatoes. Something for everyone to eat!

“Luncheon smells so good,” whispered Bee, licking her lips.

Yam pudding. My favorite! The assembly bell rang.

She pulled me around the outside of the milling crowd, whose fashionable clothing brightened the hall with so many bold colors, including intense stripes of red that matched my mounting irritation at being dragged along like baggage.

“Bee!”

“We have to get my sketchbook back. Look! There goes the old basilisk. Blessed Tanit save me. She’s giving it to the headmaster! Cat, do you have any idea—”

“I have an idea that I’m very hungry. Unlike you, I missed my morning porridge.”

“He’s seen us!”

Maestra Madrahat saw us, too, and she beckoned like an angry Astarte, goddess of war, summoning malingering troops to battle. Bee hauled. I lagged. Why ever could I not keep my mouth shut?

The headmaster was a tall, elderly black man of Kushite ancestry who had a scholarly background in the newly deciphered hieroglyphics of ancient Kemet, which the Romans felt obliged to call Egypt. The headmaster was the one person who the various monied factions in the principality of Tarrant had all agreed would, like the plants, offend no one because of his impeccably distinguished and noble Kushite lineage. Even though the great wars between Rome and Qart Hadast—called Carthage by the cursed Romans—had been fought two thousand years ago, what Kena’ani mother would actually want a son of Rome teaching her precious daughters? Our ancient feud was far from being the only dispute or duel raging in the private salons and mercantile districts of Adurnam with its many lineages, clans, ethnicities, tribes, bankers, merchants, artisans, plebeians, and lords living all smashed together in the city’s stately avenues, crowded alleys, busy law courts, and the narrow parks where hotheaded young men fought duels.

Adurnam, city of eternal quarreling!

The great port city was built along the banks of the Solent River, downstream from the vast marshy estuary we in Adurnam called the Sieve. As many rivers and tributaries and streams flowed into the Sieve as peoples, lineages, languages, gods, rhythms, and cuisines flowed into the city. So it was no wonder that the academy had chosen for its headmaster a man who could claim relation to the Kushite dynasty, whose scions had been peacefully ruling venerable but decaying Kemet—Egypt—for the last two thousand five hundred years. Even the Roman Empire had lasted only a thousand.

“Now is not a convenient time, maestra,” murmured the headmaster in a low voice I could hear, although I certainly was not meant to. “Does this matter really warrant my attention?”

“If you’ll just speak to them, maester.”

He looked toward me, as if to say with his gaze that he knew how well I could hear although we were still a thrown book away and they were speaking softly.

Bee leaned her whole body into tugging me, and we crossed the gap out of breath and staggered to a halt before him. Bee pulled off her indoor slippers, and this impulsive gesture of respect—removing shoes before an elder—made him smile. We kept our gazes humbly lowered.

“The Barahal cousins may attend me,” he said as he tucked Bee’s schoolbook under an arm. He offered a courtesy to the maestra and, leaning heavily on his cane, made his way across the hall.

Bee tugged her slippers back on and cast such a look at me. “Are you going to help me or hinder me?” she murmured.

I sighed, knowing I had no choice. Like obedient handmaidens in the old tales, we followed him out through the marble portico into the chill of the inner court, a central garden covered by a glass roof. The courtyard was surrounded on three sides by a two-storied stone building that housed classrooms, workshops, and tutors’ offices. No sun shone through the glass today; flakes of snow powdered the sloped roof. The noise of the hall behind us receded as a waiting servant opened the door to the library wing, and we entered a somewhat less chilly marble corridor. The headmaster took the wide stairs toward the upper floor, slow progress because of his infirmity. Bee’s gaze was fixed on the schoolbook under his arm in the manner of a stoat waiting for the prime instant to steal an egg.

His office was behind the first set of doors in the upper corridor. The servant, who had paced us up the steps, moved around to open these doors so the headmaster could enter without altering his steady advance. The office was spacious, with one wall of windows facing the rose court, a door into an adjoining chamber, and the rest of the wall space lined with bookcases. Mirrors hung on the back of each door, creating corridors of reflecting vision that revealed most of the chamber before and behind me.

The chamber was neither oppressively tidy nor unpleasantly messy but rather graced a middle ground between cluttered and neat. A chalkboard had been pushed in front of one bank of bookcases, facing four chairs. The large fireplace had been refitted with a circulating stove whose warmth radiated through the room. His desk had not a scrap of paper on its polished surface while the big table set beneath the windows formed a topographical masterpiece of stacked books, open books, two globes set on pedestals, and several half-unrolled maps with corners weighted down by scarabs carved out of green basalt. A longcase clock faced the table, its glass door revealing the steady motion of pendulum and weights within. Glass-doored bookcases held carefully labeled papyrus scrolls in cubbyholes classified according to chronology and subject matter.

On a pedestal in one corner was fixed the severed head of the famous poet and legal scholar Bran Cof. A scan of the chamber, as I saw it reflected within the mirrors, showed me a glimmer of magic like a cowl around the poet’s sleeping head but no other sign of magic’s presence. I caught the headmaster watching me in the mirror, though. Could he see chains of magic in mirrors, as I could? It was said that mirrors reflect the binding threads of power that run between this world and the unseen spirit world, but the truth of that statement is a secret hoarded by the sorcerers who have the power to manipulate such chains of power, people like cold mages, fire mages, druas, master poets, and the bards and djeliw. I was not one of them. I could not manipulate or handle the chains of magic except on a purely personal level: I could use them to conceal myself, to hear better, and to see in the dark. And, of course, I could see them in mirrors.

There was only one thing I remembered my mother saying to me, long, long ago, when I was five years old: Don’t tell anyone what you can do or see, Cat. Tell no one. Not ever.

I had obeyed her. I had never told anyone, except Bee, because Bee knew everything about me just as I knew everything about her.

The headmaster smiled gently at me in the mirror’s normal reflection. I looked away, because it was proper that I look away, being the student and he the elder.

“The cousins Hassi Barahal,” he observed in his dry voice, “certainly know of my admiration for the Hassi Barahal brothers.”

Naturally we knew of it, since his admiration paid our tuition.

“Your father, Beatrice, has done the academy board certain favors on whose basis your tuition is excused by the board of directors.”

“Favors” being a more palatable word for less palatable activities.

“Obviously your father’s journals, Catherine, to which your uncle has provided us full access, have proved invaluable in the academy’s quest for a deeper understanding of natural history. Daniel Hassi Barahal understood that scholars seek to unravel, explain, and explicate from scientific principles the workings of the natural world out of purely disinterested motives. That includes the mysteries of magecraft and its ties to a spirit world said to lie athwart our own. He was something of a scholar himself, if not precisely educated in the academy. Given the mage Houses’ notorious and hostile secrecy, which they can back up with actual retribution, such attempts to uncover the worlds’ workings seem bound to fail.” He paused to glance at the mirrors.

I said nothing. Neither did Bee.

“Yet we scholars are a stubborn crew. It is these circumstances—the information provided by your fathers, each in his own way—that have led me to turn a blind eye to certain reports of your behavior that are not what we would prefer to see in our female students. Allowing girls into the academy at all is controversial, so those young females who study here must conduct themselves at all times with prudence—”

A bell tinkled.

My stomach growled softly in response, but it was not the luncheon bell but a lighter handbell rung from the adjoining room. For an instant, that aged and solemn face looked startled, then concerned. As swiftly as a curtain is swept closed, he concealed his feelings beneath a meaningless polite smile.

“Wait here, maestressas.”

Still clutching Bee’s schoolbook beneath an arm, he limped to the door and, as the servant opened it, vanished into the adjoining room. We caught a glimpse of close-packed shelves of books before the servant closed the door behind both of them. Bee and I stood alone in the headmaster’s office, except, of course, for the sleeping head of Bran Cof. A rumble of voices drifted from a far chamber, but I wasn’t close enough to the inner door to pull apart the words.

“Do you think he just forgot he had it? Now what will happen?” Bee said in a low, fierce voice.

“He’ll page through and see the seven hundred small and large portraits of Maester Amadou’s pretty eyes and perfect jaw and braided hair. And before him, Maester Lewis with his red-gold hair and elevated brow and narrow chin. You’ve filled up reams of paper and ten or twelve schoolbooks with sketches of the best-looking young men in the academy.”

For once she did not spit fire. “I don’t care if people laugh at me for that. I’ve never cared what other people thought.”

True enough. “Then what matters so much to you?”

Her gusty sigh shuddered in the room, and for an instant I caught an echoing shudder of movement, eyes drifting as in dreams, beneath the closed eyelids of the poet’s head. I tensed, a shiver of cold crawling down my back, and stepped closer to Bee to clasp her hand.

What if he opened his eyes?

“I don’t know how to explain it,” she murmured, squeezing my hand. She hadn’t been looking at the head. Maybe I had imagined what I had seen. Bran Cof’s enchanted head had last been known to speak over one hundred years ago, on some arcane legal matter.

“Bee, we promised to always tell each other everything. What worries you so much about what’s in your sketchbook?”

The door into the adjoining room opened. We both jumped like children caught by the cook with honey cake stolen hot from the pan. As the headmaster’s assistant walked into the room, we offered a hasty courtesy to cover our embarrassment. His cheeks pinked—easy to see because he was albino—as he offered a more elaborate courtesy in return.

“Maestressas, I did not know you were here.” We called him the headmaster’s dog, not kindly. He hailed from a distant eastern empire beyond the Pale, and indeed one could discern his Avar heritage in his broad cheekbones and the epicanthic fold at his eyes. Rumor whispered that as a child, he had been rescued by the headmaster from death under the spears of the Wild Hunt that rode on Hallows Night. If true, the story explained his utter devotion to the old scholar.

We folded our hands politely before us and smiled at him.

For a moment, he looked ready to faint, for I am sure we appeared like two vultures biding our time until the dying cease their inconvenient thrashing. Then he glanced at Bee, his face curdling to such an unseemly shade of red that I conceived the horrible notion that the poor young man believed himself in love with her. Naturally such an infatuation was utterly forbidden between any of the teachers or their assistants and one of the academy’s prudent and virtuous female pupils, even if she was going to turn twenty and reach the age of majority in just under two months. Even if she had a mean left hook. Even if she had shown the least interest in him, which she had not.

“I beg your pardon,” Bee said so sweetly the words stung. “The headmaster instructed us to wait for him here. Will he return shortly?”

Her smile was too much for him. He croaked out a garbled word and bolted back the way he had come, wrenching the door closed behind him.

“Bee! Was that necessary?”

She stared at the door as if her gaze alone could splinter it into a thousand shards. “You know how I have always had such vivid dreams. I’ve started drawing them out to help remember them by.”

“How can you draw a dream?”

Her color was high, and her hands were clenched. “I had to try to make some sense of them because the details haunt me! I don’t even know why, and it doesn’t matter, but I can’t bear to have people looking—I can’t explain it. I didn’t even show them to you!” Tears welled in her lovely eyes. I knew when Bee was bluffing, and this wasn’t it.

I grasped her hands. “When he comes back in, you cause a distraction, anything to get him to put the book down and shift his attention elsewhere. I’ll sneak it into my schoolbag.”

Nodding, she let go my hands and wiped her cheeks. The longcase clock’s pendulum ticked. Ticked. Ticked. Ticked. Bee stared at the poet’s head as if daring Bran Cof to open his eyes. I couldn’t bear looking in case he did, so I let my gaze wander to the chalkboard. It had been recently erased, but I could still read traces of figures and words as a geologist can read down through layers of sediment and rock. The Hibernian Ice Sheet Expedition: Lost, no bodies or wreckage recovered. The Alps Ice Cap Expedition: Turned back by ice storms. The First Baltic Ice Sea Expedition: Remnants rescued after a year missing. The Second Baltic Ice Sea Expedition: Lost, no bodies or wreckage recovered.

“I wonder who that lesson was for,” said Bee. “It’s strange to look at that and remember that both your father and your mother were members of the First Baltic Ice Sea Expedition. That they were the ‘remnants rescued after a year missing.’ Them and, what, ten others?”

“Three others. Only five survived out of the twenty-eight who set out. I think I’ve read my father’s account of the opening months of that expedition a hundred times. ‘No man has ever crossed the tempestuous Baltic Ice Sea or set foot on the towering and inhospitable Skandic Ice Shelf.’ No woman, either, for that matter. Fifty-four journals he wrote and numbered. That’s the only time he mentions my mother.”

She made a face. “Probably because the next two volumes are missing.”

“Yes,” I said peevishly, “the very ones covering the rest of the expedition, when any idiot who can do math—”

“That would be you.”

“—can draw the conclusion that I was conceived in the latter months of that very expedition.”

“It is curious,” she agreed. “You would think a man falling in love would write paeans about the fine eyes of his beloved. But perhaps it was later, in the midst of the crisis on the ice, that they—”

A tremor in the floor alerted me. I lifted a hand to warn her. I heard, as she did not yet, the halting step-tap of the headmaster approaching the door. We composed our faces and pretended to be looking out the windows at the bare branches of autumn trees in the rose court. The door opened. The servant entered first, holding the door for the headmaster, who limped in with a preoccupied frown on his face. He seemed surprised to see us.

“Are you still here?” he asked. “Forgive me. I meant to dismiss you. Did I speak to you about the wisdom of not antagonizing the mage Houses, maestressas? Even in so small a way as imprudent speech?”

Bee’s eyes had gone wide as china plates, and her chin trembled. The headmaster was no longer carrying her sketchbook.

“You did, maester,” I responded promptly, seeing Bee was in no condition to speak. “I’ll guard my tongue. It was ill-considered of me. I beg pardon.”

“Ah, well, then. Best you go down to luncheon.” A smile flitted and vanished on his seamed face. “I believe there is yam pudding. My favorite!”

The servant had crossed the chamber already and opened the outer door for the headmaster. We had to follow him down the path offered.

Continues...

Excerpted from Cold Magic by Elliott, Kate Copyright © 2011 by Elliott, Kate. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

Compra usato

Condizioni: molto buonoEUR 4,50 per la spedizione da Germania a Italia

Destinazione, tempi e costiCompra nuovo

Visualizza questo articoloEUR 11,52 per la spedizione da Regno Unito a Italia

Destinazione, tempi e costiRisultati della ricerca per Cold Magic

Cold Magic (The Spiritwalker Trilogy)

Da: medimops, Berlin, Germania

Condizione: very good. Gut/Very good: Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit wenigen Gebrauchsspuren an Einband, Schutzumschlag oder Seiten. / Describes a book or dust jacket that does show some signs of wear on either the binding, dust jacket or pages. Codice articolo M0031608087X-V

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Cold Magic

Da: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condizione: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.68. Codice articolo G031608087XI4N00

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Cold Magic

Da: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condizione: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.68. Codice articolo G031608087XI4N00

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Cold Magic

Da: Buchpark, Trebbin, Germania

Condizione: Gut. Zustand: Gut | Sprache: Englisch | Produktart: Bücher. Codice articolo 10287420/3

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Cold Magic

Da: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condizione: Good. Reprint. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Codice articolo 4044007-75

Quantità: 3 disponibili

Cold Magic: 1 (Spiritwalker Trilogy)

Da: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Regno Unito

Paperback. Condizione: Good. The book has been read but remains in clean condition. All pages are intact and the cover is intact. Some minor wear to the spine. Codice articolo GOR005510359

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Cold Magic (The Spiritwalker Trilogy, 1)

Da: Bookoutlet1, Easley, SC, U.S.A.

Condizione: Very Good. Great shape! Has a publisher remainder mark. mass_market Used - Very Good 2011. Codice articolo IM-10014060

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Cold Magic (The Spiritwalker Trilogy, 1)

Da: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condizione: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Codice articolo C03E-01876

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Cold Magic

Da: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Regno Unito

Paperback. Condizione: Brand New. reprint edition. 611 pages. 6.75x4.25x1.25 inches. In Stock. Codice articolo 031608087X

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Cold Magic The Spiritwalker Tr

Da: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condizione: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Codice articolo 00091240337

Quantità: 1 disponibili