Articoli correlati a Abstract Expressionism for Beginners

Sinossi

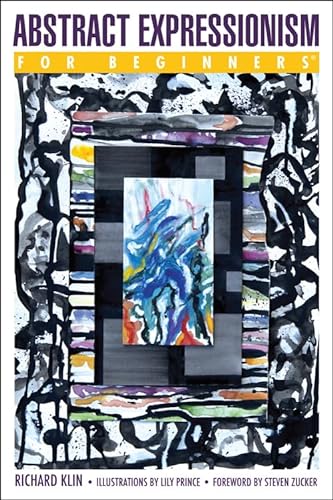

Abstract Expressionism was the defining movement in American art during the years following World War II, making New York City the center of the international art scene. But what the heck did it mean! The drips, the spills, the splashes, the blotches of color, the wild spontaneous energy--signifying what?

Abstract Expressionism For Beginners will not only help you understand, but also appreciate the art of some of the most iconic figures in modern art--Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Helen Frankenthaler, and others. Explore their lives and artistic roots, the heady world of Greenwich Village in the 1940s and 1950s, the influence of jazz, the voices of critics, and the enduring legacy of a uniquely inspired group of artists.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

Informazioni sull?autore

Estratto. © Ristampato con autorizzazione. Tutti i diritti riservati.

Abstract Expressionism

For Beginners

By Richard Klin, Lily PrinceFor Beginners LLC

All rights reserved.

Contents

Foreword by Steven Zucker,

Introduction,

Chapter 1 What Abstract Expressionism Isn't,

Chapter 2 So ... What Exactly (More or Less) Is Abstract Expressionism?,

Chapter 3 Artistic License,

Chapter 4 Worldwide Web,

Chapter 5 Let's Make a (New) Deal,

Chapter 6 Tales of Hofmann,

Chapter 7 Birth of the Cool,

Chapter 8 Jackson Pollock: The Icebreaker,

Chapter 9 Made in New York,

Chapter 10 Infinite Jest,

Chapter 11 All That Jazz,

Chapter 12 Aiding and Abetting,

Chapter 13 Artful Dodging,

Glossary,

Further Reading,

Other Resources,

About the Author and Illustrator,

CHAPTER 1

What Abstract Expressionism Isn't

Anyone searching for a precise, codified definition of Abstract Expressionism is, sadly, bound to come up short. The Abstract Expressionists were the most famous contingent of painters in the history of American art. They were emphatic about what art should and shouldn't be, but they were equally emphatic about not creating a concise, manifesto-driven movement with all the defined strictures that implied. They were going against the grain of the established art world. The established art world had definitions and rules. The Abstract Expressionists, to say the least, weren't enthralled with rules.

The very term abstract expressionism, as a matter of fact, was a label not of these painters' own choosing, but a name imposed by others. The wider art world of critics, curators, and gallery owners needed a good, shorthand tag line to describe this new, emerging school of painting. Action painting or simply the New York School came into parlance. But Abstract Expressionism — a phrase that had been floating around for a while and predated these particular painters — was the name that stuck.

Even the precise definition of who is and isn't an Abstract Expressionist is sometimes up for debate. And to muddy the waters even further, there is another group of artists called the second-generation Abstract Expressionists, who came up slightly later in the chronology.

On many levels, this vagueness of definition is the norm when it comes to new creative movements. That legendary coterie of American writers during the 1920s, for example, did not proclaim their intent to go off and create the "Lost Generation" school of literature; it was something that evolved. Likewise, the revolutionary jazz musicians who emerged after the end of World War II — musicians who, not incidentally, had a huge impact on the Abstract Expressionists — did not convene a meeting to announce to the world that a new form of jazz, called bebop, was about to be launched. The nature of artistic movements stems from creative alchemy, those unique historical and cultural circumstances when the right people come together at the right time to forge something that had never been seen or heard before. The same very much applies to the Abstract Expressionist painters. Their emergence cannot be fully explained.

Another complicating factor when it comes to truly defining Abstract Expressionism is the curve balls thrown by the painters themselves. These brash new artists consciously positioned themselves in direct opposition to the art establishment. For that matter, they consciously positioned themselves in opposition to stuffy societal mores in general. Metaphorically, they were throwing a brick into the window of the American art world. And if that brick also landed in other windows, that was okay too. Definitions, to the Abstract Expressionists, were confining, limiting. "To classify," Mark Rothko, one of Abstract Expressionism's principal talents, asserted, "is to embalm."

The painters also had disparate styles. While they shared many of the same influences and creative impulses and certainly learned from each other, the Abstract Expressionist painters had widely varying techniques and worldviews. This, too, is not uncommon when innovations in art and music come on the scene. The new wave of rock 'n roll in the 1970s, for example, is often treated as a discrete, specific movement even as that view blurs the huge distinctions between the street-smart Ramones and the art school–cerebral Talking Heads. Both bands came out at the same cultural moment, yet they were worlds apart. Likewise, the AbEx (short for AbstractExpressionism/Abstract Expressionist) painters had different backgrounds, personalities, and behavior patterns. What came out on their canvases reflected these differences. It was very much an individualist's way of approaching painting, which makes it harder to ascribe stylistic specifics to AbEx as a whole. The artists were militantly individualistic. An encapsulated definition of what they were all undertaking was intrinsically difficult: the aims and processes varied from one painter to the other.

The rough-hewn Jackson Pollock was very much a product of the American West. Willem de Kooning, raised in the Netherlands, came to the United States as a ship's stowaway. Joan Mitchell was the product of a well-heeled, artistic Chicago family. In many respects, these painters didn't have much in common. What they did have in common, of course, was crucial: The thrown brick heard 'round the art world.

CHAPTER 2So ... What Exactly (More or Less) Is Abstract Expressionism?

Abstract Expressionism may have lacked a concise definition, but the specifics far outweighed the differences: It was, after all, a discrete movement. The name itself is instructive. These were abstract painters, disregarding representational strictures. There was not much regard given to recognizable objects or even painting basics like the horizon line.

But the expressionist component was equally vital. The AbEx painters would have been horrified to have their work regarded as simply academic exercises in space and shapes, or unconventional painting simply for the sake of being unconventional. They were undertaking expressive studies in human emotion — sadness, fear, happiness — and to do these expressive studies they reached out into the greater world and into their own subconscious.

What else? The AbEx painters painted large. Many had gotten their start during the Depression, painting — under the auspices of the New Deal — large, bold murals, and this carried over into their artwork a decade later. Abstract Expressionism also took jazz's improvisatory ethos and transferred it to the canvas. They often used unconventional material, such as sign paint and collage. They were based in New York City.

The fact that they were centered in New York was vitally important for a number of reasons. The fabled city itself — massive and colorful — had a huge impact on Abstract Expressionism's collective psyche.

New York City after World War II was a teeming, frenetic place, providing enough grist for any art in any medium. With Europe in ruins, the city had emerged as the true international colossus. New York was the new Rome, with all that implied: a cacophony of highs and lows. Musicians, painters, writers, actors, and poets made their way to New York, which became a creative incubus with ample opportunity for artistic cross-pollination. It was a feast for creative types and bohemians. And it was also, of course, noisy, dirty, and poor. New York City — in all its grand contradictions — pulsated throughout much of the Abstract Expressionist oeuvre.

There was an equally significant practical aspect: The painters lived and worked in close proximity to each other. It was a concentrated space. Those sharing a like-minded worldview could interact on a constant basis (a condition that applied to all creative types, not just painters) — for better and for worse.

These upstart painters coalesced in Lower Manhattan. In a variety of ways they began to find each other. It was like sending out a beacon — sooner or later, you hope, someone flashes a light back at you. In crowded, downtown New York, the beacons flashed back and forth. In cheap cafeterias, bars, and galleries, like-minded painters bonded.

In 1949 that contingent of painters who soon emerged as the Abstract Expressionists rented a loft that became known as the Club, a place to meet and exchange ideas on a regular basis. A few years later, a seedy downtown bar called the Cedar Tavern became the legendary nexus of Abstract Expressionism, where the painters could be found night after night. The rough-and-tumble of Greenwich Village functioned as the AbEx training ground and salon.

Another key component to this movement was so overt that it risks restating the obvious: Abstract Expressionism was, well, abstract. By its very intent, it eschewed the representational and emphatically rejected the notion of painting cheery, inspirational studies of fields and mountains. Pastoral views were, of course, in short supply in New York City. (Just for the record, though, a good deal of the AbEx body of work does reference beauty and nature.) For the AbEx painters, there was a larger issue at hand. Their intent was to look elsewhere — far elsewhere, in many cases — for artistic inspiration. These painters set out in all manner of ways to dispense with conventional notions about what painting should be. Abstract Expressionist painters mined the subconscious, which was hardly a common motif in American painting. They used unconventional materials to make their artwork; some even utilized commercial paint, which was designed for use on signs and billboards. What sort of painter did that? Abstract Expressionism also incorporated music and literature into their paintings — and this was not just a passive interest. Jazz was pulsating all over New York City, just a stroll away from the artists' studios or the Cedar Tavern. It was just a stroll away from anywhere, really, which was the beauty of living in New York City.

Another common element of their aesthetic was a theoretical emphasis on the flatness of the canvas. For centuries, painters had executed their own special trickster magic: fooling the viewer into forgetting that what they were gazing at was, after all, a simple rectangular slab with paint all over it. Accordingly, painters had used the tools of their trade to convey that there was much more to be seen than a mere chunk of canvas. There was the illusion of depth, of perspective, of space, out of which new worlds could be created. The creative magic was loosely related to that of writing. In much the same way, writers historically didn't want to draw attention to the fact that a book was simply a bound stack of paper with print all over it. They didn't want to draw attention to the fact that Madame Bovary wasn't an actual person or that the events in Crime and Punishment didn't really happen. This all may sound rather obvious, but it's not. We like to lose ourselves in art and writing.

But the Abstract Expressionists were having none of that. Rather than hide the fact that a canvas was just that — a canvas — they trumpeted its flatness, putting that attribute front and center in their artistic ethos. If The Wizard of Ozbirthed the classic metaphor of not looking at the man behind the curtain, Abstract Expressionism said, "Yes, go ahead — look behind the curtain!" And partially because of this, the AbEx artists painted big: large canvases and bold, gestural brushstrokes. This decoding — pointing out that a painting was a canvas — was not solely an invention of the Abstract Expressionists. The nineteenth-century French painter Claude Monet, for example, executed large-scale paintings with an absence of the horizon line and attention to brushstrokes — traits associated with Abstract Expressionism.

If the Abstract Expressionists did not invent the flatness concept, they drove the point home, breaking down painting to its nuts and bolts. A painting, Abstract Expressionism declared, was a physical construction, a flat surface with paint. And who put that paint there? The painter. The Abstract Expressionists took full authorial responsibility. And, more often than not, the painters' personalities matched their outsized artwork.

This, too, became a central theme of the AbEx saga. The painters themselves could be eccentric, idiosyncratic, or downright weird. Many of them drank and smoked; they lived large; they burned out; some died young. Jackson Pollock was the most obvious, extreme example, but as a group, these painters were in the mold of the Beat writers, known perhaps more for their bohemianism than for their actual artistic output.

Social and political themes sometimes made their way into Abstract Expressionism, but the movement generally steered clear of overt commentary. Most of the painters did have strong political feelings, and many had been very politically active. They had witnessed the worst of the twentieth century: the Great Depression, the rise of fascism in Europe, the historic carnage of World War II. The postwar era did not seem to offer much in the way of redemption or hope. The advent of the nuclear age now meant that, with the touch of a few buttons, the entire globe could be obliterated. Anti-Communist hysteria continued to fester, and the United States was busily transforming itself into a homogenized, suburban society. All of this, to say the least, did not bode well for iconoclastic painters.

Thus, the sociopolitical aspect of Abstract Expressionism is hard to categorize — one more reason why it's hard to ascribe specific definitions to this movement. The political content is a little tricky, as befits a school of art that did its best to avoid overt definitions. Yes, some expressly political content could be found in the AbEx oeuvre. Painter and printmaker Philip Guston, for example, incorporated images of the Ku Klux Klan into his work. But in essence, the Abstract Expressionists painted what they saw metaphorically.

They were not in any way aiming for social realism. Even the most left-wing of the bunch — like Ad Reinhardt, like Barnett Newman — were overtly opposed to crafting representational paintings that depicted strikes or poor people or hopes for a better tomorrow. This was a conscious choice and therefore a little puzzling, considering how political so many of the painters were. But there it was.

What the Abstract Expressionists did explicitly portray — "explicitly," of course, in the abstract sense, which really wasn't that explicit — was a harsh, damaged world and a United States bordering on dystopia. That view would not and did not encompass specific issues. "The art that holds up the crooked mirror to the audience," Harold Rosenberg commented, "is timely not with regard to art, but with regard to society." The crooked mirror was not always pleasant to look at, but it was accurate. And it was vital. This is where Abstract Expressionism's political commentary came in: both nebulous and definite.

If nebulous and definite sounds contradictory, it is contradictory. This was part of the usual AbEx pattern: It didn't want you to get too comfortable with definitions and strictures.

CHAPTER 3Artistic License

Soon after the United States entered World War II in 1941, the Selective Service released an extensive list of semi-skilled professions that were not to be exempted from the draft. Clerks, messengers, office boys, and shipping clerks, it was specified, were required to serve. The list continued: watchmen, doormen, footmen, bellboys, pages. And sales clerks, along with filing clerks, hairdressers, dress and milliner makers, and designers. Interior decorators came next. Then — last and certainly least, underscoring its monumental unimportance — came artist.

The mere fact that the Abstract Expressionists boldly proclaimed themselves to be painters was, in and of itself, a striking development. From today's vantage point, this is difficult to comprehend: What, exactly, is the big deal about declaring yourself a painter?

In 1949 it was a very big deal. There was certainly a venerable tradition of American painting. Around the time of World War I, a cohort of American painters had begun exploring modernist motifs. The Abstract Expressionists were not operating in a total and complete vacuum. But even with all that, the beacon of modern, innovative painting came from Europe. Paris was still recognized as the international capital of the art world. In the culturally stunted United States, painting was often relegated to the side. Painters — per the Selective Service — could hang out with the bellboys and shipping clerks.

In the public mind, painters were often oddball and often foreign — and most likely amoral and foreign, two things that seemed linked. Then there was the opposite stereotype: Art lessons were the domain of old-lady teachers; painting was an activity fit only for girls and sissies.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Abstract Expressionism by Richard Klin, Lily Prince. Copyright © 2016 Richard Klin. Excerpted by permission of For Beginners LLC.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

EUR 10,41 per la spedizione da Regno Unito a Italia

Destinazione, tempi e costiCompra nuovo

Visualizza questo articoloEUR 2,31 per la spedizione da Regno Unito a Italia

Destinazione, tempi e costiRisultati della ricerca per Abstract Expressionism for Beginners

Abstract Expressionism For Beginners

Da: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Regno Unito

Paperback. Condizione: Very Good. Prince, Lily (illustratore). The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Codice articolo GOR009590335

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Abstract Expressionism For Beginners

Da: WeBuyBooks, Rossendale, LANCS, Regno Unito

Condizione: Very Good. Prince, Lily (illustratore). Most items will be dispatched the same or the next working day. A copy that has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Codice articolo wbs3054926380

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Abstract Expressionism for Beginners

Da: Rarewaves.com UK, London, Regno Unito

Paperback. Condizione: New. Prince, Lily (illustratore). Codice articolo LU-9781939994622

Quantità: 13 disponibili

Abstract Expressionism for Beginners

Da: Rarewaves.com USA, London, LONDO, Regno Unito

Paperback. Condizione: New. Prince, Lily (illustratore). Codice articolo LU-9781939994622

Quantità: 13 disponibili

Abstract Expressionism For Beginners

Da: Kennys Bookshop and Art Galleries Ltd., Galway, GY, Irlanda

Condizione: New. Prince, Lily (illustratore). Illustrator(s): Prince, Lily. Series: For Beginners. Num Pages: 176 pages. BIC Classification: ACXD9. Category: (G) General (US: Trade). Dimension: 155 x 287 x 14. Weight in Grams: 320. . 2016. Paperback. . . . . Codice articolo V9781939994622

Quantità: 1 disponibili

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM FOR BEGINNERS

Da: Speedyhen, London, Regno Unito

Condizione: NEW. Prince, Lily (illustratore). Codice articolo NW9781939994622

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Abstract Expressionism for Beginners

Da: PBShop.store UK, Fairford, GLOS, Regno Unito

PAP. Condizione: New. Prince, Lily (illustratore). New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Codice articolo GB-9781939994622

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Abstract Expressionism For Beginners

Da: Kennys Bookstore, Olney, MD, U.S.A.

Condizione: New. Prince, Lily (illustratore). Illustrator(s): Prince, Lily. Series: For Beginners. Num Pages: 176 pages. BIC Classification: ACXD9. Category: (G) General (US: Trade). Dimension: 155 x 287 x 14. Weight in Grams: 320. . 2016. Paperback. . . . . Books ship from the US and Ireland. Codice articolo V9781939994622

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Abstract Expressionism for Beginners

Da: Revaluation Books, Exeter, Regno Unito

Paperback. Condizione: Brand New. Prince, Lily (illustratore). 176 pages. 9.25x6.00x0.75 inches. In Stock. Codice articolo __1939994624

Quantità: 2 disponibili

Abstract Expressionism for Beginners

Da: THE SAINT BOOKSTORE, Southport, Regno Unito

Paperback / softback. Condizione: New. Prince, Lily (illustratore). New copy - Usually dispatched within 4 working days. 352. Codice articolo B9781939994622

Quantità: 1 disponibili