An advisor to Italian publishing houses, a translator of Freud and Jung, a friend of Montale and Calvino, Roberto Bazlen was nothing if not a literary man, but kept his writings to himself.

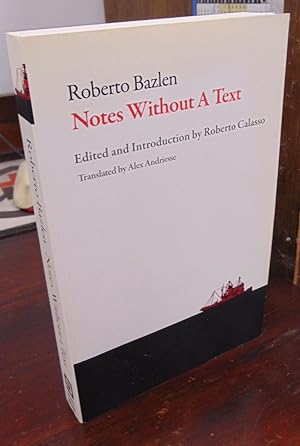

Here, translated into English for the first time, the reader will discover Bazlen’s private oeuvre: an unfinished novel, The Sea Captain, which bears comparison with the fiction of Kafka and Beckett; a selection of entries from his notebooks dealing with topics as various as whether or not there is an “animal Jahweh” and the aesthetic limitations of the cinema; a trio of essays on his native city of Trieste; and a sampling of his editorial letters. Notes Without a Text is an introduction to the work of one of the unknown masters of twentieth-century European literature.

FROM THE SEA CAPTAIN (a novel)

The sea captain’s house was old and comfortable. There were hydrangeas in the windows, a canary was singing in its cage, the captain’s wife was sitting at her sewing machine, a dog was playing with a bone by the door.

The captain didn’t spend much time at home. He was almost always at sea, and at sea he sat alone in his big cabin, he studied nautical charts, he fumbled with his precision instruments, he read little-known books whose trails he followed from port to port—otherwise, he stood on the deck and scanned the horizon, for hours on end, with his telescope. If he arrived in a port where he’d never been before—but there were so few!—he immediately began wandering aimlessly about, on the steps he chatted up the fishwives, he tasted unfamiliar wines in tucked-away taverns, he went nosing about, through dark and twisting alleys, in the dusty shops of the junk dealers. By the time he went back aboard, he had seen everything, he had taken note of everything, he had formed an idea of everything, and in his cabin he opened the packages full of plants, stones, books, bottles of wine, and wooden statuettes. But, for one reason or another, these things were never the right things, and this made him more and more restless. He was sometimes overwhelmed by a sudden nostalgia for his wife and his life at home; when he returned, he would kiss his wife, he would pet his dog, and he would listen patiently to all the things that had happened in his absence; but his eyes wandered impatiently out the window, and his mouth hardened whenever ships, in the distance, passed by on the sea. And always he went back to his table by the globe, and set it slowly spinning.

p>Once, he had stayed at sea for longer than usual. When he came back home, his wife gave him a kiss and her breath was sweet. With a smile, she said:

“I’ve had to wait for you such a long time. While I was waiting, I sewed you a pair of red trousers. Let me show them to you.”

And her voice was clear.

The captain was always very courteous. He thanked his wife and glanced at the trousers. But to himself he said: “My wife doesn’t understand me. I’m a sea captain, the trunks in my cabin are crammed full of perfectly ironed uniforms—white for summer, blue for winter—and here, in the wardrobe, hangs my black suit, the one I wear to weddings and funerals. What am I supposed to do with red trousers?” He locked up the trousers in the black chest, but he sensed that something was wrong, and he began slowly spinning the globe. The next day he spoke a few ritual words to his wife, gave her a quick kiss goodbye, then fled. And he stayed at sea for even longer than he had the last time.

But this time his wife did not sit at the sewing machine.

“Why should I sew?” she asked herself. “He didn’t even bother to look at the trousers; he just locked them up in the black chest, after I’d taken so much trouble with them. He doesn’t understand me anymore.”

She opened the chest, ran her hands over the trousers, and felt very sad. The day was empty, she began rummaging through the chest and found a box of cigars. And she thought disdainfully:

“If he doesn’t want to wear my trousers, then I’ll smoke his cigars.”

And she lit a cigar, stared out the window, and blew reeking black smoke out toward the sea, which smelled of salt.

In those days, the One-Eyed Man had come to live in the city. Passing by the Captain’s house, he looked up with his single eye at the woman in the window and said:

“Women who smoke cigars play cards too!”

“Certainly,” the woman answered. “Come up then and we’ll play together.”

And soon they were sitting down to play every day. The woman won and smoked her cigar, the One-Eyed Man lost and wore a look of contentment.

When, after a long absence, the Captain returned, he gave his wife a kiss, but her breath was no longer sweet, and her voice had grown hoarse. “My wife has become a stranger,” the Captain thought, but he said nothing and continued to act as courteously as ever. Except he fled even sooner and stayed at sea even longer than he had the last time.

One day, in the harbor tavern, the One-Eyed Man told the Craterface what he was doing with the Captain’s wife.

“You ought to bring her down here one of these days,” said the Craterface. “Women who smoke cigars and play cards drink grappa too.”

And soon the woman found herself sitting in the tavern every day, smoking cigars and playing cards. She went home late in the evenings, staggering drunkenly, and in the morning she lazed in bed

When the Captain finally returned, the hydrangeas had withered in the windows. Nevertheless, he gave his wife a kiss, but her breath stank of tobacco and grappa and her voice had gone gravelly. He said to himself: “This time, not even for form’s sake, there’s no way I’m giving her a kiss goodbye.” And he went away again at once, and he stayed at sea even longer than he had the last time.