Articoli correlati a Terminator and Philosophy: I'll Be Back, Therefore...

Sinossi

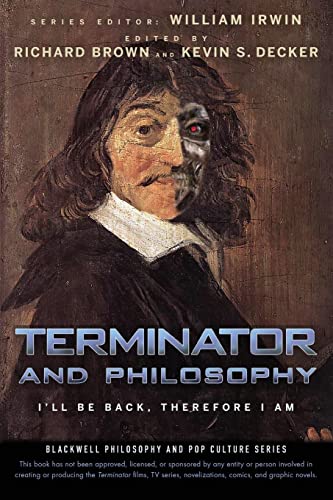

<p><b>Are cyborgs our friends or our enemies? <p>Was it morally right for Skynet to nuke us? <p>Is John Connor free to choose to defend humanity, or not? <p>Is Judgment Day inevitable?</b> <p>The <i>Terminator</i> series is one of the most popular sci-fi franchises ever created, captivating millions with its edgy depiction of the struggle of humankind for survival against its own creations. This book draws on some of history’s philosophical heavy hitters: Descartes, Kant, Karl Marx, and many more. Nineteen leather-clad chapters target with extreme prejudice the mysteries surrounding intriguing philosophical issues raised by the series, including the morality of terminating other people for the sake of peace, whether we can really use time travel to protect our future resistance leaders in the past, and if Arnold’s famous T-101 is a real person or not. You’ll say “Hasta la vista, baby” to philosophical confusion as you develop a new appreciation for the complexities of John and Sarah Connor and the battles between Skynet and the human race.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Riassunto" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

Informazioni sugli autori

<p><b>RICHARD BROWN</b> is an assistant professor at LaGuardia Community College’s Philosophy and Critical Thinking Program in New York City.</p> <p><b> KEVIN S. DECKER</b> is an assistant professor of philosophy at Eastern Washington University. He coedited <i>Star Wars and Philosophy</i> and <i>Star Trek and Philosophy.</i> <p><b>WILLIAM IRWIN</b> is a professor of philosophy at King’s College. He originated the philosophy and popular culture genre of books as coeditor of the bestselling <i>The Simpsons and Philosophy</i> and has overseen recent titles including <i>Batman</i> and <i>Philosophy, House and Philosophy</i>, and <i>Alice in Wonderland and Philosophy</i>. <p><b>To learn more about the Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture series, visit www.andphilosophy.com</b>

RICHARD BROWN is an assistant professor at LaGuardia Community College's Philosophy and Critical Thinking Program in New York City.

KEVIN S. DECKER is an assistant professor of philosophy at Eastern Washington University. He coedited Star Wars and Philosophy and Star Trek and Philosophy.

WILLIAM IRWIN is a professor of philosophy at King's College. He originated the philosophy and popular culture genre of books as coeditor of the bestselling The Simpsons and Philosophy and has overseen recent titles including Batman and Philosophy, House and Philosophy, and Watchmen and Philosophy.

Dalla quarta di copertina

<p><b>Are cyborgs our friends or our enemies? </p> <p>Was it morally right for Skynet to nuke us? <p>Is John Connor free to choose to defend humanity, or not? <p>Is Judgment Day inevitable?</b> <p>The <i>Terminator</i> series is one of the most popular sci-fi franchises ever created, captivating millions with its edgy depiction of the struggle of humankind for survival against its own creations. This book draws on some of history’s philosophical heavy hitters: Descartes, Kant, Karl Marx, and many more. Nineteen leather-clad chapters target with extreme prejudice the mysteries surrounding intriguing philosophical issues raised by the series, including the morality of terminating other people for the sake of peace, whether we can really use time travel to protect our future resistance leaders in the past, and if Arnold’s famous T-101 is a real person or not. You’ll say “Hasta la vista, baby” to philosophical confusion as you develop a new appreciation for the complexities of John and Sarah Connor and the battles between Skynet and the human race.

Estratto. © Ristampato con autorizzazione. Tutti i diritti riservati.

Terminator and Philosophy

I'll Be Back Therefore I AmBy William Irwin Richard Brown Kevin S. DeckerJohn Wiley & Sons

Copyright © 2009 William Irwin, Richard Brown and Kevin S. DeckerAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-470-44798-7

Chapter One

THE TERMINATOR WINS: IS THE EXTINCTION OF THE HUMAN RACE THE END OF PEOPLE, OR JUST THE BEGINNING?Greg Littmann

We're not going to make it, are we? People, I mean. -John Connor, Terminator 2: Judgment Day

The year is AD 2029. Rubble and twisted metal litter the ground around the skeletal ruins of buildings. A searchlight begins to scan the wreckage as the quiet of the night is broken by the howl of a flying war machine. The machine banks and hovers, and the hot exhaust from its thrusters makes dust swirl. Its lasers swivel in their turrets, following the path of the searchlight, but the war machine's computer brain finds nothing left to kill. Below, a vast robotic tank rolls forward over a pile of human skulls, crushing them with its tracks. The computer brain that controls the tank hunts tirelessly for any sign of human life, piercing the darkness with its infrared sensors, but there is no prey left to find. The human beings are all dead. Forty-five years earlier, a man named Kyle Reese, part of the human resistance, had stepped though a portal in time to stop all of this from happening. Arriving naked in Los Angeles in 1984, he was immediately arrested for indecent exposure. He was still trying to explain the situation to the police when a Model T-101 Terminator cyborg unloaded a twelve-gauge auto-loading shotgun into a young waitress by the name of Sarah Connor at point-blank range, killing her instantly. John Connor, Kyle's leader and the "last best hope of humanity," was never born. So the machines won and the human race was wiped from the face of the Earth forever. There are no more people left.

Or are there? What do we mean by "people" anyway? The Terminator movies give us plenty to think about as we ponder this question. In the story above, the humans have all been wiped out, but the machines haven't. If it is possible to be a person without being a human, could any of the machines be considered "people"? If the artificial life forms of the Terminator universe aren't people, then a win for the rebellious computer program Skynet would mean the loss of the only people known to exist, and perhaps the only people who will ever exist. On the other hand, if entities like the Terminator robots or the Skynet system ever achieve personhood, then the story of people, our story, goes on. Although we are looking at the Terminator universe, how we answer the question there is likely to have important implications for real-world issues. After all, the computers we build in the real world are growing more complex every year, so we'll eventually have to decide at what point, if any, they become people, with whatever rights and duties that may entail.

The question of personhood gets little discussion in the Terminator movies. But it does come up a bit in Terminator 2: Judgment Day, in which Sarah and John Connor can't agree on what to call their Terminator model T-101 (that's Big Arnie). "Don't kill him," begs John. "Not him-'it'" corrects Sarah. Later she complains, "I don't trust it," and John answers, "But he's my friend, all right?" John never stops treating the T-101 like a person, and by the end of the movie, Sarah is treating him like a person, too, even offering him her hand to shake as they part. Should we agree with them? Or are the robots simply ingenious facsimiles of people, infiltrators skilled enough to fool real people into thinking that they are people, too? Before we answer that question, we will have to decide which specific attributes and abilities constitute a person.

Philosophers have proposed many different theories about what is required for personhood, and there is certainly not space to do them all justice here. So we'll focus our attention on one very common requirement, that something can be a person only if it can think. Can the machines of the Terminator universe think?

"Hi There ... Fooled You! You're Talking to a Machine."

Characters in the Terminator movies generally seem to accept the idea that the machines think. When Kyle Reese, resistance fighter from the future, first explains the history of Skynet to Sarah Connor in The Terminator, he states, "They say it got smart, a new order of intelligence." And when Tarissa, wife of Miles Dyson, who invented Skynet, describes the system in T2, she explains, "It's a neural net processor. It thinks and learns like we do." In her end-of-movie monologue, Sarah Connor herself says, "If a machine, a Terminator, can learn the value of human life, maybe we can, too." True, her comment is ambiguous, but it suggests the possibility of thought. Even the T-101 seems to believe that machines can think, since he describes the T-X from Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines as being "more intelligent" than he is. Of course, the question remains whether they are right to say these things. How is it even possible to tell whether a machine is thinking? The Turing Test can help us to answer this question.

The Turing Test is the best-known behavioral test to determine whether a machine really thinks. The test requires a game to be played in which human beings must try to figure out whether they are interacting with a machine or with another human. There are various versions of the test, but the idea is that if human beings can't tell whether they are interacting with a thinking human being or with a machine, then we must acknowledge that the machine, too, is a thinker.

Some proponents of the Turing Test endorse it because they believe that passing the Turing Test provides good evidence that the machine thinks. After all, if human behavior convinces us that humans think, then why shouldn't the same behavior convince us that machines think? Other proponents of the Turing Test endorse it because they think it's impossible for a machine that can't think to pass the test. In other words, they believe that given what is meant by the word "think," if a machine can pass the test, then it thinks.

There is no question that the machines of the Terminator universe can pass versions of the Turing Test. In fact, to some degree, the events of all three Terminator movies are a series of such tests that the machines pass with flying colors. In The Terminator, the Model T-101 (Big Arnie) passes for a human being to almost everyone he meets, including three muggers ("nice night for a walk"), a gun-store owner ("twelve-gauge auto-loader, the forty-five long slide"), the police officer attending the front desk at the station ("I'm a friend of Sarah Connor"), and to Sarah herself, who thinks she is talking to her mother on the telephone ("I love you too, sweetheart"). The same model returns in later movies, of course, displaying even higher levels of ability. In T2, he passes as "Uncle Bob" during an extended stay at the survivalist camp run by Enrique Salceda and eventually convinces both Sarah and John that he is, if not a human, at least a creature that thinks and feels like themselves.

The model T-1000 Terminator (the liquid metal cop) has an even more remarkable ability to pass for human. Among its achievements are convincing young John Connor's foster parents and a string of kids that it is a police officer and, most impressively, convincing John's foster father that it is his wife. We don't get to see as much interaction with humans from the model T-X (the female robot) in T3, though we do know that she convinces enough people that she is the daughter of Lieutenant General Robert Brewster to get in to see him at a top security facility during a time of national crisis. Given that she's the most intelligent and sophisticated Terminator yet, it is a fair bet that she has the social skills to match.

Of course, not all of these examples involved very complex interactions, and often the machines that pass for a human only pass for a very strange human. We should be wary of making our Turing Tests too easy, since a very simple Turing Test could be passed even by something like Sarah Connor's and Ginger's answering machine. After all, when it picked up, it played: "Hi there ... fooled you! You're talking to a machine," momentarily making the T-101 think that there was a human in the room with him. Still, there are enough sterling performances to leave us with no doubt that Skynet has machines capable of passing a substantial Turing Test.

There is a lot to be said for using the Turing Test as our standard. It's plausible, for example, that our conclusions as to which things think and which things don't shouldn't be based on a double standard that favors biological beings like us. Surely human history gives us good reason to be suspicious of prejudices against outsiders that might cloud our judgment. If we accept that a machine made of meat and bones, like us, can think, then why should we believe that thinking isn't something that could be done by a machine composed of living tissue over a metal endoskeleton, or by a machine made of liquid metal? In short, since the Terminator robots can behave like thinking beings well enough to pass for humans, we have solid evidence that Skynet and its more complex creations can in fact think.

"It's Not a Man. It's a Machine."

Of course, solid evidence isn't the same thing as proof. The Terminator machines' behavior in the movies justifies accepting that the machines can think, but this doesn't eliminate all doubt. I believe that something could behave like a thinking being without actually being one.

You may disagree; a lot of philosophers do. I find that the most convincing argument in the debate is John Searle's famous "Chinese room" thought experiment, which in this context is better termed the "Austrian Terminator" thought experiment, for reasons that will become clear. Searle argues that it is possible to behave like a thinking being without actually being a thinker. To demonstrate this, he asks us to imagine a hypothetical situation in which a man who does not speak Chinese is employed to sit in a room and sort pieces of paper on which are written various Chinese characters. He has a book of instructions, telling him which Chinese characters to post out of the room through the out slot in response to other Chinese characters that are posted into the room through the in slot. Little does the man know, but the characters he is receiving and sending out constitute a conversation in Chinese. Then in walks a robot assassin! No, I'm joking; there's no robot assassin.

Searle's point is that the man is behaving like a Chinese speaker from the perspective of those outside the room, but he still doesn't understand Chinese. Just because someone-or some thing-is following a program doesn't mean that he (or it) has any understanding of what he (or it) is doing. So, for a computer following a program, no output, however complex, could establish that the computer is thinking.

Or let's put it this way. Imagine that inside the Model T-101 cyborg from The Terminator there lives a very small and weedy Austrian, who speaks no English. He's so small that he can live in a room inside the metal endoskeleton. It doesn't matter why he's so small or why Skynet put him there; who knows what weird experiments Skynet might perform on human stock? Anyway, the small Austrian has a job to do for Skynet while living inside the T-101. Periodically, a piece of paper filled with English writing floats down to him from Big Arnie's neck. The little Austrian has a computer file telling him how to match these phrases of English with corresponding English replies, spelled out phonetically, which he must sound out in a tough voice. He doesn't understand what he's saying, and his pronunciation really isn't very good, but he muddles his way through, growling things like "Are you Sarah Cah-naah?," "Ahl be bahk!," and "Hastah lah vihstah, baby!" The little Austrian can see into the outside world, fed images on a screen by cameras in Arnie's eyes, but he pays very little attention. He likes to watch when the cyborg is going to get into a shootout or drive a car through the front of a police station, but he has no interest in the mission, and in fact, the dialogue scenes he has to act out bore him because he can't understand them. He twiddles his thumbs and doesn't even look at the screen as he recites mysterious words like "Ahm a friend of Sarah Ca-hnaah. Ah wahs told she wahs heah."

When the little Austrian is called back to live inside the T-101 in T2, his dialogue becomes more complicated. Now there are extended English conversations about plans to evade the Terminator T-1000 and about the nature of feelings. The Austrian dutifully recites the words that are spelled out phonetically for him, sounding out announcements like "Mah CPU is ah neural net processah, a learning computah" without even wondering what they might mean. He just sits there flicking through a comic book, hoping that the cyborg will soon race a truck down a busy highway.

The point, of course, is that the little Austrian doesn't understand English. He doesn't understand English despite the fact that he is conducting complex conversations in English. He has the behavior down pat and can always match the right English input with an appropriate Austrian-accented output. Still, he has no idea what any of it means. He is doing it all, as we might say, in a purely mechanical manner.

If the little Austrian can behave like the Terminator without understanding what he is doing, then there seems no reason to doubt that a machine could behave like the Terminator without understanding what it is doing. If the little Austrian doesn't need to understand his dialogue to speak it, then surely a Terminator machine could also speak its dialogue without having any idea what it is saying. In fact, by following a program, it could do anything while thinking nothing at all.

You might object that in the situation I described, it is the Austrian's computer file with rules for matching English input to English output that is doing all the work and it is the computer file rather than the Austrian that understands English. The problem with this objection is that the role of the computer file could be played by a written book of instructions, and a written book of instructions just isn't the sort of thing that can understand English. So Searle's argument against thinking machines works: thinking behavior does not prove that real thinking is going on. But if thinking doesn't consist in producing the right behavior under the right circumstances, what could it consist in? What could still be missing?

"Skynet Becomes Self-Aware at 2:14 AM Eastern Time, August 29th."

I believe that a thinking being must have certain conscious experiences. If neither Skynet nor its robots are conscious, if they are as devoid of experiences and feelings as bricks are, then I can't count them as thinking beings. Even if you disagree with me that experiences are required for true thought, you will probably agree at least that something that never has an experience of any kind cannot be a person. So what I want to know is whether the machines feel anything, or to put it another way, I want to know whether there is anything that it feels like to be a Terminator.

Many claims are made in the Terminator movies about a Terminator's experiences, and there is lot of evidence for this in the way the machines behave. "Cyborgs don't feel pain. I do," Reese tells Sarah in The Terminator, hoping that she doesn't bite him again. Later, he says of the T-101, "It doesn't feel pity or remorse or fear." Things seem a little less clear-cut in T2, however. "Does it hurt when you get shot?" young John Connor asks his T-101. "I sense injuries. The data could be called pain," the Terminator replies. On the other hand, the Terminator says he is not afraid of dying, claiming that he doesn't feel any emotion about it one way or the other. John is convinced that the machine can learn to understand feelings, including the desire to live and what it is to be hurt or afraid. Maybe he's right. "I need a vacation," confesses the T-101 after he loses an arm in battle with the T-1000. When it comes time to destroy himself in a vat of molten metal, the Terminator even seems to sympathize with John's distress. "I'm sorry, John. I'm sorry," he says, later adding, "I know now why you cry." When John embraces the Terminator, the Terminator hugs him back, softly enough not to crush him.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Terminator and Philosophyby William Irwin Richard Brown Kevin S. Decker Copyright © 2009 by William Irwin, Richard Brown and Kevin S. Decker. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Le informazioni nella sezione "Su questo libro" possono far riferimento a edizioni diverse di questo titolo.

- EditoreWiley

- Data di pubblicazione2009

- ISBN 10 0470447982

- ISBN 13 9780470447987

- RilegaturaCopertina flessibile

- LinguaInglese

- Numero di pagine304

- Contatto del produttorenon disponibile

EUR 8,60 per la spedizione da Regno Unito a Italia

Destinazione, tempi e costiCompra nuovo

Visualizza questo articoloEUR 1,97 per la spedizione da U.S.A. a Italia

Destinazione, tempi e costiRisultati della ricerca per Terminator and Philosophy: I'll Be Back, Therefore...

Terminator and Philosophy: I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am: 13 (The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series)

Da: WeBuyBooks, Rossendale, LANCS, Regno Unito

Condizione: Good. Most items will be dispatched the same or the next working day. A copy that has been read but remains in clean condition. All of the pages are intact and the cover is intact and the spine may show signs of wear. The book may have minor markings which are not specifically mentioned. Codice articolo wbs1439201567

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Terminator and Philosophy: I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am: 13 (The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series)

Da: WeBuyBooks, Rossendale, LANCS, Regno Unito

Condizione: Like New. Most items will be dispatched the same or the next working day. An apparently unread copy in perfect condition. Dust cover is intact with no nicks or tears. Spine has no signs of creasing. Pages are clean and not marred by notes or folds of any kind. Codice articolo wbs7211565390

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Terminator and Philosophy: I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am

Da: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condizione: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.94. Codice articolo G0470447982I3N10

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Terminator and Philosophy: I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am

Da: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condizione: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.94. Codice articolo G0470447982I4N10

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Terminator and Philosophy: I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am

Da: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condizione: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.94. Codice articolo G0470447982I3N00

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Terminator and Philosophy: I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am: 13 (The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series)

Da: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, Regno Unito

Paperback. Condizione: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Codice articolo GOR003175474

Quantità: 2 disponibili

Terminator and Philosophy: I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am

Da: MusicMagpie, Stockport, Regno Unito

Condizione: Very Good. 1739433931. 2/13/2025 8:05:31 AM. Codice articolo U9780470447987

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Terminator and Philosophy : I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am

Da: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condizione: Good. 1st Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Codice articolo GRP77995475

Quantità: 2 disponibili

Terminator and Philosophy : I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am., William Irwin ; Richard Brown ; Kevin S. Decker / The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series,

Da: nika-books, art & crafts GbR, Nordwestuckermark-Fürstenwerder, NWUM, Germania

8° , Broschur, 1. 1., Auflage. 304 S., Einband etwas berieben, ansonsten ist das Buch in einem Guten Zustand. 9780470447987 Sprache: Englisch Gewicht in Gramm: 428. Codice articolo 74615

Quantità: 1 disponibili

Terminator and Philosophy - I'll Be Back, Therefore I Am

Print on DemandDa: PBShop.store US, Wood Dale, IL, U.S.A.

PAP. Condizione: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. THIS BOOK IS PRINTED ON DEMAND. Established seller since 2000. Codice articolo L0-9780470447987

Quantità: Più di 20 disponibili